Memorial

HIC EXEUNT CABALLI DE NAVIBUS ET HIC MILITES FESTINAVERUNT HESTINGA, UT CIBUM RAPERENTUR (“HERE THE HORSES ARE GETTING OUT OF THE BOATS AND HERE THE SOLDIERS HAVE SPED TO HASTINGS TO SEIZE FOOD”)

by Alison Kinney

I

I do not think seventy years is the time of a man or woman,

Nor that seventy millions of years is the time of a man or woman,

Nor that years will ever stop the existence of me, or any one else.— Walt Whitman, “Who Learns My Lesson Complete?”

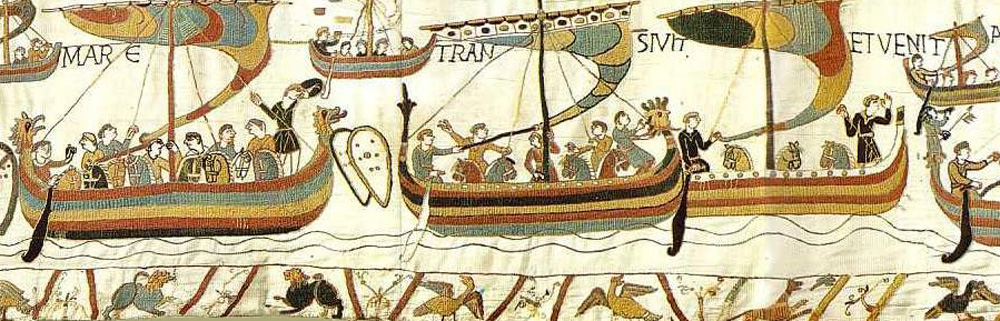

The masterpiece—the war memorial, wall hanging, apologia—tells the same old story, a case of do or die: a tale of friends betrayed, cross-Channel invasion, and the passage of a comet heralding the doom of old England. No sooner had the Normans conquered England in 1066 than Bishop Odo of Bayeux, half-brother and regent of William the Conqueror, commissioned a documentary to legitimize and commemorate his fellow overlords’ rule of the Anglo-Saxons. That great work is the textile formerly known as the Tapisserie de Bayeux, or the Bayeux Tapestry.

That it’s been called a tapestry at all has something to do with the gendered labor of medieval textile production—while men wove tapestries, women stitched embroideries—and a great deal to do with the gendered labor of scholarship. For the sake of peace, about which the textile doesn’t have much to say, let’s just call it the Bayeux Embroidery. It’s a seventy-by one-half-meter length of linen panels worked in crewel, its madder-, mignonette-, and woad-dyed yarns still as vivid, after a thousand years, as the tints of the Art Nouveau comic strip Little Nemo. From one antic, cartoon-like scene to the next march the triumphant William and the defeated Harold (sporting a dastardly mustache), along with their troops, horses, and hounds. Here, “HIC” in the Latin inscriptions, “HAROLD:DVX:TRAHEBAT:EOS:DE ARENA”: Duke Harold extracts the Normans, then still his allies, from treacherous sands. HIC, William deforests northern France to build ships; HIC, his fleet sails from the mouth of the Somme to assail the English coast; HIC, he feeds his troops skewer-roasted poultry. HIC, the birds and mythical beasts of the Embroidery’s lower border give way to a motif of soldiers’ limbs, hacked and trampled at the Battle of Hastings. “HIC CECIDERVNT SIMUL:ANGLI ET FRANCI:IN PRELIO”: here the English and French have fallen together in battle.

Invoking the thirteenth-century philosopher Duns Scotus’s idea of “haecceitas,” thisness, medievalist Valerie Allen writes about the Bayeux Embroidery’s “dynamic things grounded in space and time,” “from kitchen utensils to war gear…. [O]bjects acquire a kind of agency by exerting their inherent ‘virtue’, wearing down conventional distinctions between human and non-human to the point that a hand, a sword and a relic can all share in the same phenomenal luminosity.” The Embroidery itself is just such a luminous agent: a war memorial—a Normandy Beach war memorial, no less. In this place occupied by hundreds of memorials, planned and incidental, fleeting and obdurate, from funerary sculpture to the bunkers that, after seventy years of coastal weather, still bear flamethrowers’ char marks, memorials develop unpredictable, unaccountable vibrancies that can shape the conflicts, even the topography, of later battles. That is, if they can first escape violence, neglect, and ordinary wear and tear.

Carola Hicks’ book The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece chronicles the Embroidery’s survival of the 1562 Calvinist sack of Bayeux, the French Revolution’s requisitioning it as a wagon cover, misbegotten restoration techniques, and, nearly a millennium after its creation, redeployment as a standard of war. In 1803, dreaming of reconquering England, Napoleon mounted a Paris exhibition of the Embroidery and subsidized a Théâtre du Vaudeville operetta about it, La Tapisserie de la Reine Mathilde (Queen Mathilde’s Tapestry). During World War II, the Ahnenerbe, the Nazi institute for cultural pseudo-science, exploited the Embroidery’s “new evidence for the culture-bearing power of our Germanic traditions” to legitimize their geopolitical ambitions. Just before the 1944 German surrender of Paris, while Hitler shrieked for the city’s annihilation, Himmler radioed the Gestapo an urgent reminder to loot the Embroidery from its lead case in the basement of the Louvre.

Meanwhile, Rea Irvin’s cartoon for the July 15, 1944 cover of The New Yorker mimicked the Embroidery’s style to celebrate the Allied Invasion of Normandy: “MARE NAVIGAVIT: D·DAY·JVNE VI.” The magazine cleverly adapted the imagery, while committing a cringe-worthy faux pas. In a week when British and Canadian forces in Normandy were still dying by the thousands at the battle for German-occupied Caen, the cartoon raised the specter of the catastrophic, ignominious defeat of the English at Hastings. As the Embroidery has it, “ET FVGA:VERTERVNT ANGLI”: the English turned tail and fled, men and horses bolting right off the edge of the fabric.

Today, the Centre Guillaume-le-Conquérant confines the Embroidery under shatter-proof glass, so schoolchildren and art historians can’t hurt it, and so the Embroidery—hostage, collaborator, turncoat, and mascot to multiple armies—can’t get out to hurt them. Like all such testaments, the Embroidery is both repository and maker of memory: source of the facts we resolve into histories, participant in the worlds that designed it and inherited it, tribute to and bearer of war. Not all memorials are as volatile as the World War I Verdun battlefield, where thousands of tons of unexploded ordnance still threaten the lives of farmers, hikers and deminers. But accidents of history, defying all expectation, can vivify the most quiescent monuments. Granite and iron shatter, cities burn to the ground, yet flax and wool endure centuries of abuse, theft and damp, to furnish instructions for a new regime’s mobilization.

When William the Conqueror launched his eleventh-century building campaign [1] in the city of Caen [2], he probably didn’t think he was setting the terms for his own capital’s ruin. Among other projects, including a whopping castle, he built the Church of Saint Étienne to house his tomb, steps away from the perfectly good tenth-century Church of Saint Étienne, which was decommissioned, abandoned, and dubbed “Le Vieux” (The Old). William’s city on the hill, constructed of bright cream-colored Jurassic limestone, advertised its splendor and might, its domination of the Channel and the river Orne’s travel and trade routes, to invaders and occupiers who knew a good thing when they saw it: Edward III and Henry V of England during the Hundred Years’ War. The Huguenots, who broke into William’s tomb and scattered his bones, of which only one femur was ever recovered. And the Nazis.

The bombed church at St. Étienne de Caen. Photograph by Karl Steel

Although the Allies had hoped to capture Caen on D-Day itself, the German occupation withstood two months of battle, which incurred 2,000 civilian and 50,000 Canadian and British troop casualties and leveled seventy percent of the city. Seventy-one years later, amidst a new cityscape of modernism and period reconstruction, William’s Saint Étienne still stands, daring enemies to take shots at it with weaponry inconceivable in William’s time. Nearby, the unsalvageable, bombed-in husk of poor Saint-Étienne-le-Vieux sprouts with wind-borne grasses that have mistaken the eaves for cliffs, as they did in Proust’s [3] tribute to a coastline soon to be deranged by world war. Any or none of these relics—Old and Less Old church, mid-century apartment complexes—might serve as the memorials, or the strongholds, of the next millennium.

II

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say ‘To-morrow is Saint Crispian:’

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

And say ‘These wounds I had on Crispin’s day.’

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day….—William Shakespeare, Henry V

Omaha Beach is a long curve of waves and gently sloped, golden-gray sand. The sand blows into eyes and mouths; it looks, feels, and tastes like ordinary sandcastle sand. Perhaps only hounds and doves might sense the disturbance here, a force far below the threshold of human perception: the sand is magnetic. Its grains are quartz, feldspar, limestone, and shell, and iron shrapnel, and tiny, spherical beads of iron and mineral-infused glass generated by shockwaves. They’re the incidental residue of the largest [4] seaborne invasion of all time, when thousands died and 13,000 bombs pulverized the coast. Unique, finite and irreplaceable, shifting in the flow of waves, tides, and storms, the sands attest to a day when molten iron and rock mingled with salt water and blood.

To the east towers the promontory, Pointe du Hoc, where two battalions of U.S. Rangers, equipped with ropes and grapples, suffered 135 casualties in their attempt to scale the sheer thirty-meter-high cliffs. Their objective: to seize the German artillery battery at the top. The battery site, a plain studded with incongruous yellow wildflowers in spring, is scarred with hundreds of craters, some measuring twenty feet deep: the round pits of aerial bombs, the teardrop-shaped pits of naval shells hurled laterally from vessels in the Channel. Amidst the devastation, the bunker and gun pits remain as eerily vacant as they were on D-Day, when those Rangers who survived their climb discovered that the Germans had long since absconded with their guns.

These are the landscapes of “Ozymandias”—not Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem, but that of historical novelist and stockbroker Horace Smith, who took on Shelley in a sonnet competition. While Shelley may have written the last word on despotic vanity and “the decay / Of that colossal wreck” where “Nothing beside remains,” Smith wrote:

We wonder — and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours — when thro’ the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chase,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

Published one month after Shelley’s poem in Leigh Hunt’s magazine The Examiner, Smith’s “Ozymandias,” which he retitled “On A Stupendous Leg of Granite, Discovered Standing by Itself in the Deserts of Egypt, with the Inscription Inserted Below,” doesn’t entirely deserve its relegation to literary footnote status. We might stop to wonder at Smith’s ambition to time travel into the apocalyptic future of London, evoking the imaginative force that relics hold over later generations: what Smith’s Hunter sees, in the absence of any other record, is the unmistakable, stupendous exertion of power.

When a “fragment huge” of marble or verse withstands the Säuberung, falò, ransack, or firestorm that consumes other works—museums, libraries, literary magazines—sometimes it’s by chance. Sometimes, it’s by incidental or intentional endorsement of the powers lighting the bonfires. The Embroidery earned its wartime safe house because it was a masterpiece, but also because it served as ad campaign and war propaganda, proclaiming the inevitability of conquest. Its themes recur in the neoclassical WWII Commonwealth Bayeux Memorial, whose frieze declares, “NOS A GULIELMO VICTI VICTORIS PATRIAM LIBERAVIMUS”: We, conquered by William, have liberated the Conqueror’s land. The text is boastful, arch, rueful, gracious, dark and affectionate all at once, and, in its elegant arc from loss to victory, it perpetuates the myth of inevitable martial redemption, erasing such messiness as Dunkirk, or Henry V’s 1415 massacre of the French at Agincourt. Besides, Henry was a descendant of William the Conqueror—and soldiers from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa are buried at the Memorial—so who were “we,” anyway?

Memorials must make choices. Selectivity limits and enables all representational forms; the brain’s suppression of some memories is essential to the retention of others. But the language of war, and of memorial committees, selects who “we” are, whom “we” have subjugated, who is memorable, and whose memory we suppress, choices of strategic omission and planned oblivion.

Among the 9,387 white marble grave markers at the massive Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial at Colleville-sur-Mer, one stone commemorates a man who died twenty-one years before the outbreak of WWII: Lieutenant Quentin Roosevelt, killed in the First World War, reinterred by his family beside his brother, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. That the Roosevelts should have secured this honor, repurposing the cemetery as their family plot, was only one small way that power and memorials regenerate each other. Another was the marking of 307 graves of the unknown dead—“Here rests in honored glory a comrade in arms known but to God”—with crosses. Not with the Stars of David that mark 149 other graves. Not with any other shape that might have questioned the imposition of Christian identity as a normative default, after a war that had killed millions of people deemed non-normative and unmemorable. [5]

At the American Cemetery, the white marble dazzles the eye. Visitors murmur, ritually, predictably, “Never forget,” echoing the cries for the victims of the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center—and also the rallying cries for the War on Terror. They summon up other memorials: the dark, perpetually falling waters in New York; the commemorative T-shirts and snow globes; and the 9/11 “Never Forget” mural at Camp Echo, in a country, Iraq, innocent of the attacks. Memorial is mourning, is a weapon, is official policy and official lie, is mourning for the policies and lies. That memorial sites elicit a slogan so implicated in a hundred thousand civilian deaths suggests that their “inherent virtue” is an infinite, aimless toxicity. Perhaps memorials should be barricaded behind the multi-millennial warning systems designed for nuclear waste sites, to repel civilizations 250,000 years from now from the death rays.

And yet. Unsanctioned possibilities subvert the American Cemetery’s attempt to marshal order and heroism out of a terrain saturated with death. Beneath the doggedly mown lawns lie millions of bones. The solemn, clean-lined monuments to unknown soldiers evoke carnage that could not be apportioned to specific graves. The very nature of this place is unconstraint: the overflow of bodies and gold-lettered names, the overflow of capital and political will expended to make war look dignified, containable, and, when the sun shines on the reflecting pool, beautiful. These are not the least of war’s excesses, or of its monumentality: monumental waste, monumental suffering, monumental power to perpetuate itself in beautiful lies and obliteration.

Just possibly, even the incantation of “Never forget” in such a place might rupture the continuity of martial remembrance. Because the phrase originates in the commemoration of Holocaust victims, its redeployment substitutes one mass grave for another and another—9/11, Virginia Tech—begetting amnesia from a plea for awareness. Its repetition in Normandy vacates all specific remembrance, except for the appeal to remember…what? We forget what we’re supposed to remember, even during the length of a D-Day jeep tour. Seventy or seven hundred years from now, perhaps dulled repetition will also vacate the phrase’s allegiance to violence and revenge, leaving only the memory of grief.

Memorials raise hackles, offering grounds for resistance to war, jingoism, and stupendous power. They speak indiscriminately to mourners, comrades, partisans, veterans, dissenters, peacemakers—groups of overlapping, porous membership—to those who come in rage or grief, or to learn. If erasure is inextricable from memory, dissent seizes on the lack of completion, naturalness, and neutrality in its selections. Donald De Lue’s big bronze statue of a white man, “The Spirit of American Youth Rising From the Waves,” coexists with the graves of Private First Class Mary J. Barlow, PFC Mary H. Bankston, and Sergeant Dolores M. Browne of the WAC 6888th Central Postal Directory Battalion. The Six Triple Eight were the only all-women, all-African-American battalion deployed in WWII; they traveled overseas, served, and were forced to operate their own mess hall, housing, and motor pool under segregation rules. The American Cemetery honors the three women on terms of representative equality denied them during their service and in their lives back home: that is something else a memorial can do. But the crosses tell only their names, ranks, dates, and states, not their stories. We must look elsewhere to find more; we must make and remake memory in turn. We remember, we wonder.

ici git guil. (“Here Lies William”).William the Conqueror’s tomb at the new church of Saint-Étienne de Caen. Photograph by Karl Steel

III

Like when god throws a star

And everyone looks up

To see that whip of sparks

And then it’s gone

—Alice Oswald, Memorial

On October 25, 1915 in Pas-de-Calais, French officers invited their British fellows to a parade followed by a battlefield tour and reception to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt—some 75 kilometers from the Western Front. The London Illustrated News lauded the “nobly inspired,” “chivalrous spirit” of the event: “There could, surely, be no more convincing or finer testimony to the reality of the brotherhood-in-arms now so fortunately established between the soldiers of France and Britain, and the closeness of the tie between the nations, than this joint celebration of an ancient battle-day of honourable memory to both.” The News doesn’t speculate about what Henry V, or the vanquished Charles VI of France, would have made of this display of friendship, propaganda, and weirdness, or how the brothers-in-arms reckoned it [6] the following year, when the Battle of the Somme churned out one million casualties.

HIC CECIDERVNT SIMUL:ANGLI ET FRANCI:IN PRELIO.

As time goes by, the remaining WWII veterans will no longer strip their sleeves to show their scars, yet the memorials of their deeds will draw crowds for D-Day’s 75th anniversary, maybe the 750th. Although memorials survive as precariously and arbitrarily as we do, when they endure, they defy frail human powers. Unconstrained by news cycles, human attention, or lifespans, they operate on timescales grander and more frightening. The memorial through time offers the terrifying—but, remotely, liberating—possibility that rocks, textiles, and castles, and ideologies, injustices, and cults of power, might change.

The cliffs backing the D-Day beaches contain the fossils of Jurassic ammonites. The grass still grows there, indifferent to our lost time. After WWII, Pointe du Hoc became a topographical monument, to the U.S. Rangers, and also to failed military intelligence and needless, awful sacrifice. But this memorial that so harshly confronts the victory narrative is made of the most fragile of mediums: coastline. Supporters raised $6 million to fund preservation work projected, optimistically, to halt erosion until around 2060. But that estimate was made in 2010, before the latest, direful climate change prognostications. Someday, not in the unimaginably distant future, Pointe du Hoc will crumble and wash away, along with the magnetic sands of Omaha Beach. Another maritime monument, the Allies’ floating port of Mulberry Harbour, now consists only of the cracking, eroding concrete caissons of the breakwater. The caissons will keep testifying to this feat of wartime engineering, constructed and fully operational within days of the Invasion, only if another barrier is built to protect them. The breakwater’s name: Phoenix.

Time creates of memorials a palimpsest of ruins upon ruins; old memories undergo the indignities and transfigurations of force, revision, and water. Pointe du Hoc may not outlast all those who were alive on D-Day, but already, it’s telling a new story about rising sea levels and storms, wealth and ideological priorities, and global recklessness. What will Trajan’s Column say a millennium from now, or Trayvon Martin’s memorial in Sanford, Florida? We launch our memorials, as time capsules—ravens or doves—or bombs—into unknown futures, bearing our faults and stories, not knowing which will crumble or rot, be swallowed by weeds, mounted in museums, or blasted. We can’t predict whether, freshly restored, they’ll urge future soldiers to kill, or mourn another war intended to end all wars. We don’t know which to preserve and which to let slip into the waves, in anticipation of a future that may make all our remembrance completely irrelevant, or only too purposeful.

In 1942, a wartime film that Variety called “splendid anti-Axis propaganda” and The New Yorker called “pretty tolerable” featured a love anthem, “As Time Goes By.” Playing “the same old story / A fight for love and glory,” for a war the U.S. had entered only the year before, the song recast uncertainty as recollection, offering resolutions to an unforeseeable denouement, and, of course, elisions. Originally, when Herman Hupfeld wrote it for the 1931 not-getting-a-Broadway-revival-any-time-soon musical Everybody’s Welcome, it included a prelude fretting about Einstein’s theory of relativity.

This day and age we’re living in

Gives cause for apprehension

With speed and new invention

And things like fourth dimension.

Dooley Wilson, who played Sam, doesn’t sing the prelude in Casablanca. If he had, the film would have ushered an atomic future into Rick’s Café: the practical applications of special relativity, the genocide at Nagasaki and Hiroshima. It’s just a show tune, the way Cassandra was just a killjoy. If we bothered to look up, sing, and stage the prelude, we might learn something about a pop song’s apprehension of the half-lives of atoms and memories, Cold War and Iraq War. But we don’t. The prelude is even more fundamental than love, glory, and beautiful friendship: anticipating disaster, and relegated to a footnote of Broadway history, omitted from the admonition “You must remember this.”

That we were afraid, yet our fears were already forgotten: that, too, is what memorials tell. In text, textile, bronze and sand, they bear the weight of cumulative fear and futility, atrocities effaced from official memory, generations who wept or cheered at war’s return. We embed them in the earth—they emerge from bloodbaths—we chain stitch their contours, marking failure.

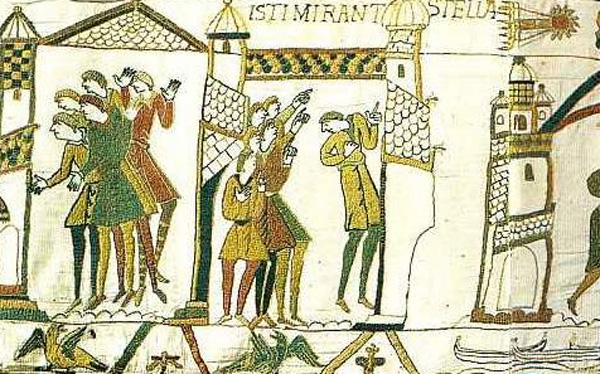

When Halley’s Comet lit the nighttime skies of March 1066, the Anglo-Saxon monk (and designer of flying machines) Eilmer of Malmesbury reportedly cried, “You’ve come, you source of tears to many mothers, you evil. I hate you! It is long since I saw you; but as I see you now you are much more terrible, for I see you brandishing the downfall of my country. I hate you!” A later fellow of the same abbey, William, recounted Eilmer’s prophecy of the Norman Conquest in his Gesta regum Anglorum. William wrote with the benefit of hindsight, and, again, the allure of narrative arc, but his Eilmer speaks from the depths of an old man’s reminiscence, which encompasses more disaster—literally, the “ill-starred”—than any comet can bring.

ISTI MIRANT STELLA(M) (“THESE MEN WONDER AT THE STAR”)

The Embroidery, commissioned by Normans but stitched by Anglo-Saxons in Canterbury, depicts the comet as a ball of fire, a mini-sun, emitting what looks like a stream of rocket propellant. It zooms perilously close to Harold’s head. “ISTI MIRANT STELLAM”: they wonder at the star. Then come the ships. The onslaught of cavalry. The hail of arrows. And, in one of the few appearances of women in the Embroidery, “HIC DOMVS:INCENDITVR”: here a house is burned. As soldiers set torches to her roof, as the flames leap, a little veiled woman emerges from the wreckage, leading a child by the hand. You must remember this.

When 3066 marks the 2000th anniversary of the Norman Conquest, the Bayeux Embroidery may still be telling its tale of heaven-borne doom. It has shaped and endured wars when bombs arced through the skies, wars threatening rockets and weapons of mass destruction. It endures an age of drone warfare, when death closes in on its victims as that star did to Harold. Perhaps this cloth, which has outlasted kings, kingdoms and stones, will survive another millennium to tell wonder tales of the inscrutable past, when we fought wars and carved memorials to them, when we despaired of ever learning from memory, when disaster still illuminated the sky, forcing tears from mothers’ eyes.

Notes:

[1] Caennaise Charlotte Corday read Rousseau and Voltaire in the school library of William’s Abbaye aux Dames.”

[2] During the bombardment, the Caennais in the temporary hospital at the Bon Sauveur convent were saved by nurse Danièle Clément-Heintz, who flew a red-crossed flag from the roof: a sheet dipped in blood. Thanks to Gregory Curtis for his family history.

[3] à côté de sa coupole, ce clocher que, parce que j’avais lu qu’il était lui-même une âpre falaise normande où s’amassaient les grains…

[4] Its 1,260 merchant vessels alone outstripped the fabled Greek invasion of Troy.

[5] The Caen-Normandy Memorial Centre for History and Peace commemorates victims of the Holocaust, including Roma victims. It was the first museum outside the U.S. to display mementoes of the World Trade Center attacks. It does not have an exhibit on Algeria.

[6] What would they make of the Emily Blunt film Edge of Tomorrow, where the WWI Western Front and WWII Battle of Normandy are won via memories of two infinitely repeated days of battle? Or the upcoming reenactment at Agincourt’s 600th-anniversary?

Works Referenced:

Madeline H. Caviness, “Anglo-Saxon Women, Norman Knights and a ‘Third Sex’ in the Bayeux Embroidery”; Valerie Allen, “On the Nature of Things in the Bayeux Tapestry and Its World”; and Dan Terkla, “From Hasting to Hastings and Beyond: Inexorable Inevitability in the Bayeux Tapestry,” in The Bayeux Tapestry: New Interpretations, ed. Martin K. Foys, Karen Eileen Overbey, and Dan Terkla (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2009).

Carola Hicks, The Bayeux Tapestry: The Life Story of a Masterpiece (New York: Vintage, 2007).

About the Author:

Alison Kinney’s book of cultural history, Hood, will be published by Bloomsbury’s “Object Lessons” series in January 2016. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, The Mantle, Narratively, Hyperallergic, Avidly, New Criticals, and other publications.