Rolling Lines

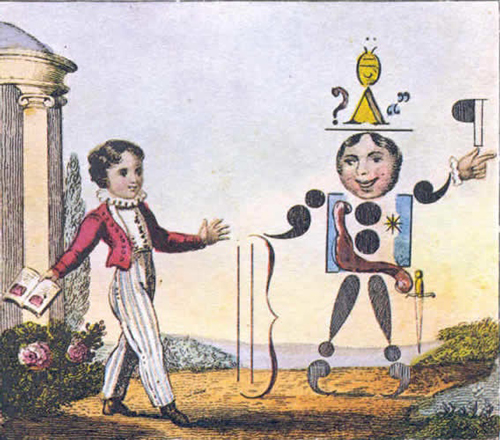

Punctuation Personified, John Harris, 1824

On writing (and not writing)

by rob mclennan

I have spent most of the past two decades in daily ritual, waking to immediately sit with notebook, drafts of various works-in-progress, and a mound of reading material. Work comes from the accumulation: the momentums of routine, patience and attention. I do not write in quick bursts but in a succession, even a sequence, of bursts. What I accomplish today is but a segment. Was William Carlos Williams a better poet because he wrote semi-distracted poems onto prescription pads? Was his inattention boiled down to bursts of pure focus?

I attempt to pay attention, but it sometimes overwhelms.

“More things interrupt my work,” Leonard Cohen wrote, slipping into an early poem. Sometimes the interruption is the work itself, requiring a simple break of breath. I step away from my desk to spend a weekend in Toronto, as far away from the comfort of writing as possible. We pack the car and head out, achieving little in the way of work, but a sequence of distracted thoughts.

Some days are Orpheus: I can’t look back, for fear of losing everything.

I attempt to sharpen a book about my late mother, attempt to complete a collection of short stories. I aim for completion somewhere over the next six months; perhaps a year. I am attempting to write about that which I do not yet know.

I sometimes feel in such a hurry I haven’t even time to mention it.

There are days I require to put all aside, and simply read. These are becoming more prominent. These are grounding, rejuvenative. Distractions that do not take away from the work, but instead become the work.

I sit on the back deck and slip into what I wouldn’t have time for, otherwise. Last summer, the eight-hundred-page Richard Brautigan biography. Currently, recent prose works by Ali Smith and Lynn Crosbie. I sit, ignore the pull of the internet or the telephone. There are the squirrels that bounce up the railings, the silence of neighbourhood cats as they prowl. I ignore the collection of unfinished short stories and yet, through distraction, end up composing six pages of notes into a new short story.

“Don Quixote,” the novel that I perpetually hope to return to, once these other two prose projects are completed. I am thinking about the sketches I’ve made so far on my birth mother. I am sketching her into a shape; amorphous, still.

A decade ago, Margaret Christakos and I discussed the importance of wasting time, hours that allow somehow to sort out what might even follow; what we had each hoped for our growing children. Without wasting time, we might otherwise get nothing done. The same trick applies to composition: years I wrote hours on Greyhound, VIA Rail, Air Canada, simply because there was nothing else I could have done. New ideas came quick, and notebooks filled themselves, between drifts off into sleep.

The balance between focused work and distracted else.

Laundry and dishes and recycling: done. A quick wipe of the kitchen counter. Don’t have to worry about the garbage or changing Lemonade’s litter until tomorrow.

Large fiction projects require a deeper attention, away from the flurry of short reviews, essays, poems, poems and poems. I have to shift my focus, sustained for a series of days that turn into weeks, if anything real is to become accomplished.

I stare into the distance, lost in a flurry of thought. Sometimes I roll a line around in my head, shaping a sharpness of phrase before committing to paper.

I’ve done enough to recognize the need for patience. All in good time.

Infinite Chakras: a Trans-Temporal Mini-Memoir

by j/j hastain

Writing is collaboration between spirit and matter.

A long time ago, while the beautiful david wolach was telling me about poems about Anna Akhmatova and swans and I was thinking about bones being liquefied, I was asked by them what spirit even means. The first part of the jolt toward answering was stillness. I literally felt still inside. Then, the words: “The ineffable, an infinity of chakras, a cosmos-consciousness as inarguable intelligence by which many lenses and language wefts and wafts come into focus, a focus that can go on forever.”

Paper drafts of wind drafts. Elemental drafts of elementals.

I have always preferred the journals in which, based on how the paper is made, the paper is not refined of its texture. I write in a journal that gives me literal splinters in my hands. Working with paper, working with the body, working with memory, all as bridges between spirit and matter (bridges herein, meant to emphasize where the two fuse and then overlap, not that the two are somehow separate) is a work in which I depend on feeling.

My long-time emphasis on feeling as mystical–elemental, and treated as such (by me) as a form of enablement in form, comes from how much of my memory consists of other-planar information. When you are in a human body, but are recalling experiences, senses, commitments, even sagacious swagger, fromother realms (both in and outside of the human body), the result can be a hounding dysphoria. What am I to do with the fact that I know the flaming door in the forest wood, even somatically recall its heat, far more than I feel familiarity with any door in my childhood home or at a friend’s house? How will I relate to doors?Further, what of the fact that my gender (for me gender is a mystical site from which various embodiments are composed for the sake of the body as communion and resonance with cosmos-consciousness) is so feral, yet so discernible in the context of merge? In our intimacy, if you are this, then I know the that that I am, automatically, based on the contour, based on what makes the hinge of us grow fur or fruit.

My framework is not frameless, though it is a freed frame: an infinity of chakras. This infinity involves immeasurable energy centers, each capable of being tuned up in order to assist with spiritual and magical work. How did I earn this perspective? Through lifetimes of devotion particular to fostering a vast view? Through rites which required so much of me, that I was literally stripped to bareness in Underworld after Underworld like Inanna? Through pledging myself to the queer corona?

I trust these chakras like I trust a friend or a lover. In other words, I lean my entire weight into them. I have worked for them, after all. Are these chakras, worlds, populated by unseen beings? If so, are they also grounded by human beings who travel to them, astrally? When I dream of one chakra as a pastoral permeation, as a site in which a weaver can weave any form of cosmos materiality (from gold to dark matter) together into a wand (or dick) shape, am I dreaming my own memoir of this human life?

For me, writing is the commitment (in form) to communion with mysteries by way of the devotion required in order to follow the gnaw/ draw to create into an actual composition. Where devotion meets materiality can result in form being made! In addition to the devotion necessary in order for ephemeral architectures to be built, in order for these renovations of polluted socio-cultural configurations to take place, I commit to the fact that pages are trees. In the most basic sense, my writing is a root system that quests for various form and spirit symbiosis (with the cosmos (roots that climb the sky) as well as with the actual earth itself). Let’s just sit for a moment in the trees, call them forth to our consciousness while we ponder what trees might in fact feel for our pages.

Whether by stitching fragments, or following sound spools toward gatherings of matter on the page, whether bowing to the incarnation, the life-force present in collages, whether allowing myself to be possessed by the plentitude of data in the unseen but adjacent realm, (a realm by which I am being instructed or cautioned or even cleaved to), I am always just trying to ignite and then foster a passionate relation with the land (until it reaches the place of flourish, until the land senses itself as blessed by me).

Mysteries are holistic. They go into and renovate caught or traumatized pockets in socio-cultural agenda—that radically alter the ways that those pockets have negative impacts on our bodies. Wholesome involvement with the planet cures schisms regarding not always feeling at home here. Why do I not always feel at home? As a queer, I am literally not at home in the context of conservative and exclusivist agenda, as a queer woman I am literally not at home in the context of patriarchy. As a being who works with the unseen realms and leans into them as much if not more as I lean into human relationships, I am definitely placed on the outskirts (by social norms and social expectations). As a person who knows that talking to myself is a way of communing with the divine, as a shaman of merge who actively brings outskirt-inhabitants (road kill, queers, unseen beings, mystics, etc.) into a circle, into a fold, I am definitely taking a different train than most. I believe my body is for this, and, due to my long-time commitment to them, my body is inseparable from pages. Pages as compassions of thought, as compassions of commissure.

When I get a rejection from a publisher—or even when I get an angry rejection letter from a publisher asking me what the fuck I think I am doing–when I get feedback from someone who reads one of my book and says “What is this? Is this stream of consciousness?”—how am I to respond? Do I say, “Yes, it is a beings’ stream and it was meant for you to not only wade in, but get naked in, run amok during dusk when an entire year’s worth of road kill owls hoot and holler from the trees above you—it was meant for you to enter it, get into it, not stand on the side and deliberate some confusion about it.” Do I lovingly chagrin? Or do I just see myself as a solitary and nod to a cookie cutter rejection, go and find a literal or another metaphorical cave in which to practice, to keep practicing?

I have been practicing with precise intent since I was a child. I have always had synesthesia and synesthesia has been integral to my synthesis, my spiritual and matter-based practices. Synthesis as a patchwork bond between myself and myself, between myself and another, between this realm and that one. Am I a peace maker between here and else? Am I chord-weaver? Is my body in a ready posture of servitude (of these realms in an effort at alleviating disparateness or discrepancy for the sake of what resounding, mixed thing could exist in its place) a form of cosmic glue?

I am clearing the infinite chakras of residue, of shame. I am dreaming round energy nodes that I can treat as master glyphs. Where a queer writing meets a queer attunement meets this queer body, comes an awareness by way of side-gates: side-gates that while finding (divining) ways to open them, provide clarifying rites just prior to the portal.

Crucial features within an approximate fate.

Th Attack of Difficult Prose

by Gail Scott

I cop here the title of Charles Bernstein’s essay Attack of the Difficult Poems to talk briefly about Difficult Prose. I am not inclined to use the word fiction; if there is fictional transformation in certain prose that I and others make, it borrows heavily from poetry and collapses distinctions between text and commentary. Nor is this prose part of the wave of currently much discussed aggregate computer generated text, although all work–even when falsely parading under the rubrique of individual artifact–is now generally acknowledged to be dependent to some degree on some form of collectively generated language. But then any work has always been dependent on some degree of collective generation–which is why sometime in the early 20th, well before the intersection of the making of art and digital technologies, people started questioning the position of the hero author. It is important to remember that that questioning of authorship was enhanced in the heat of the collective radical politics of May 68, etc. So why, of all “creative” writing forms, does the novel still dominate the collective literary palate with requisite author and narrator heroes or anti-heroes, gathering reader energy into the transparency of their imposing narrative arc? I want to say–actually I want to scream–when I try to read media reviews—inevitably about novels ultimately programmed to passify or distract, marketed with tags of “brilliant,” “soaring,” “poignant”–I want to say: take your thumb out of your mouth. Marguerite Duras is more elegant: There are often narratives but very seldom writing. And Bernstein, more empathetic: …I see the fate of all of us as related to a lack of judgment, a lack of cultural and intellectual commitment, on the part of the PWC (publications with wide circulation). It is possible that online media is already ringing mainstream market-oriented criticism’s death knell. Still, I long for the time when writers thumbed their noses at bad “criticism.” There is a hilarious interview of Margaret Atwood, dated 1977 in the CBC archives, suggesting on national TV that interviewer Hana Gartner would be better off reading Harlequin romances. This, in response to Gartner’s gripe that she cannot empathize with Atwood’s depressing stories. Atwood is no difficult writer but she is a rare Canadian literary figure who has not hesitated to don the mantle of bitch when the situation required.

I am fascinated by the question of intersections between codes, languages, genres, genders, classes—if there is an intersection, there I am in the middle. To think about the little-travelled crossroads where Bernstein’s fated “us (poets/difficult writers)” intersects with a sparse public uninterested in writing that is formally or otherwise strange-making is to underscore how to write is to converse, whatever the platform. The enviable conversations I imagine among such Canadian poets as, say, Wah, Zolf, Robertson, Bök, Cree poet Halfe, Neveu, and so on re: form, practice, politics–has little parallel in Canada’s small dispersed experimental prose field. Fortunately the digital revolution allows for countless variants of aggregate authorship–including nurturing influencies across geographies. My writing and thinking about prose is continually renewed as a result of immediate textual connections and displacements with experimental prose writers mostly to the south. These writers, in their writing and in their criticism (Renee Gladman, Bob Gluck, Stacy Szymaszek, Carla Harryman, Rachel Levitsky, to name a few) are, one way or the other, lifting the novel, a heavy thing, into a space closer to both poetry and the essay. But conversations across borders do not a critical milieu make as regards the cultural specifics and issues in the corner one occupies ; I worry that the fragmented nature of culture north of the 49th functions as an impediment to a form of prose potentially heuristic regarding notions of citizenship here.

It is true that I have a very specific notion of what makes prose experimental–and that is the formal dispersal of the writing subject. On either side of the border, queer, feminist, and anti-racist concerns have borrowed poetic and rhetorical devices to challenge the old fashioned and politically questionable (anti-)heroics of the official novel; and, on both sides of the border, there is a serious reader-reception problem. As the younger gay New York writer Douglas A. Martin writes: “In reviews of my I-driven works, I am put to defend my use of (a) conceptual self, provisional, in a way a poet would not be….” Ergo, the reader (hugely abetted by PWC criticism) will not tolerate language that gets in the way of reassuringly transparent identitary-in-all-senses-including psychological narrative logic. Curiously, the intersection of queer/feminist and other minority issues with aesthetic and literary genre issues has opened a post-identitary prose space in which the subject, the speaking ‘I’, the “narrator,” is in fact not stable, has at the very least burnt edges, is shredded, is hopelessly porous, is conceptual. In other words, Martin, in his writing, positions his writing subject in diagonal to his personal identity issues. In my own work, in all my novels since Heroine, the breaking down of the writing subject has been critical to the shape of the work. It is a mighty struggle to accomplish this “poetic” writing subject when working with a sentence, including a sentence not necessarily contiguous in the narrative sense. But some of us feel this effort is a socially and aesthetically essential exercise in our era. I am drawn by the elegance, the rightness of that writing that both searches out [reflects on] BUT ALSO devours [destroys] its identity issues, which are its every day.

To work with sentences is to imply a wish for some kind of “working out” over the length of the text—a working out that vaguely suggests a somewhat embodied subject. But it is to be stressed that “character” and “narrator” in the prose I am talking about are written into the structure, the grammar, the syntax of the work—they intersect with rather than represent or describe the “real.” I find the poet Rilke’s experiments with reading coronal suture, as reported by media theorist Friedrich Kittler, a useful figure for the author of experimental prose. A trace or a groove appears where the frontal + parietal bones of the suckling infant have grown together, wrote Rilke. As if, commented Kittler, the discoveries of Freud and Exner had been projected out of the brain onto its enclosure, so that the naked eye is now able to read the coronal suture as a writing of the real. All you have to do is apply a gramophone needle—I am thinking here of the needle as a writing tool–to these coronal sutures, or to any anatomical surface (says Kittler) and what they yield, upon replay, is a primal sound without a name, music without notation, a sound ever more strange than any incantation for the dead for which the skull might have been, originally, used. Instead of making melancholic associations using the skeleton as metaphor, like, say, Hamlet—the sounds—initially traced by Rilke as markings on a cylinder, could then be reproduced analogically. These physiological traces implied, for me, in the wake of Rilke, that our own nervous system, “our own body is a map of the outside world.” With its street markings, its dark corners, its multiple identities, its white noise from the past; and its repressed, denied, sometimes scurrilously resuscitated desirata, my so-called narrator, ever on the cusp between “inner” and “outer,” is destined to be endlessly recomposing as she ostensibly moves towards a future novel end. In what we are currently calling experimental prose, the projection of a conceptual-provisional speaking subject still rubs, both in pan-national and minority discourses, against an apparent need for solid identity tropes. As a poet friend, who is also an arts adminstrator, put it recently:

I used to think poets had it bad. Now I believe that experimental prose writers are at the bottom of the barrel.

Essays first published at Ottawa Poetry Newsletter. Gail Scott’s essay first appeared at Matrix Magazine.

About the Authors:

Born in Ottawa, Canada’s glorious capital city, rob mclennan [photo credit: Christine McNair] currently lives in Ottawa. The author of more than twenty trade books of poetry, fiction and non-fiction, he won the John Newlove Poetry Award in 2011, and his most recent titles are the poetry collections Songs for little sleep, (Obvious Epiphanies, 2012), grief notes: (BlazeVOX [books], 2012), A (short) history of l. (BuschekBooks, 2011),Glengarry (Talonbooks, 2011) and kate street (Moira, 2011), and a second novel, missing persons (2009). A new work of fiction, The Uncertainty Principle: stories,(Chaudiere Books) will be out sometime this winter. An editor and publisher, he runsabove/ground press, Chaudiere Books (with Jennifer Mulligan), The Garneau Review, seventeen seconds: a journal of poetry and poetics and the Ottawa poetry pdf annual ottawater. He spent the 2007-8 academic year in Edmonton as writer-in-residence at the University of Alberta, and regularly posts reviews, essays, interviews and other notices at robmclennan.blogspot.com

j/j hastain is a collaborator, writer and maker of things. j/j performs ceremonial gore. Chasing and courting the animate and potentially enlivening decay that exists between seer and singer, j/j, simply, hopes to make the god/dess of stone moan and nod deeply through the waxing and waning seasons of the moon. She is the inventor of The Mystical Sentence Projects and is author of several cross-genre books including the trans-genre book libertine monk (Scrambler Press), The Non-Novels (forthcoming, Spuyten Duyvil) and The Xyr Trilogy: a Metaphysical Romance of Experimental Realisms. j/j’s writing has most recently appeared in Caketrain, Trickhouse, The Collagist, Housefire, Bombay Gin, Aufgabe andTarpaulin Sky.

Gail Scott writes experimental prose and essays and Fred Wah calls her a poet. Her last novel The Obituary was a finalist for the Grand Prix du Livre de Montréal (Montréal Book Prize).