Set the World on Fire

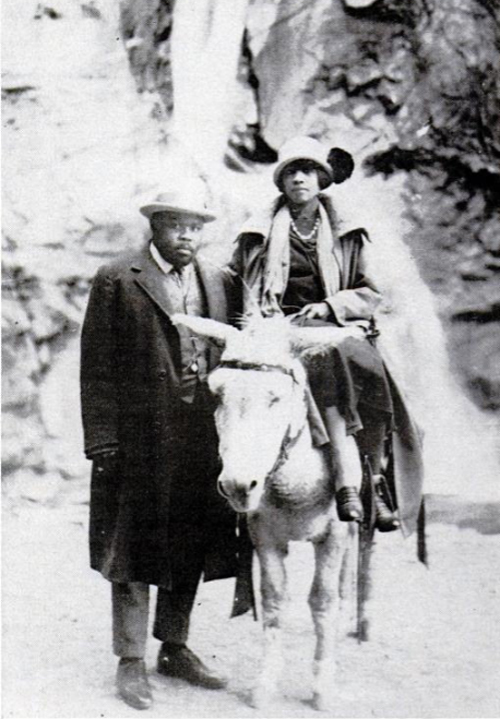

Amy Jacques Garvey with her husband, Marcus Garvey, 1922

by Nicholas Grant

Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom,

by Keisha N. Blain,

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 264 pp.

In 1937, the black nationalist activist Celia Jane Allen packed her bags and headed from Chicago to Mississippi. Working for the Peace Movement of Ethiopia (PME), she traveled against the tide of the Great Migration with the specific aim of promoting black emigration to West Africa. Allen addressed black audiences throughout Mississippi, disseminating letters and articles from PME founder Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, establishing new local chapters, and even collaborating with prominent white supremacist senator Theodore Bilbo. Over six years, she risked her life to promote the black nationalist values of race pride, political self-determination, and economic independence in the Jim Crow South. Insisting that black men and women had no future in the United States, she noted that during this chapter of her life, “I tried very hard to make my people see that our time is winding up in the Western World” (p. 91).

Allen is just one of several absorbing and multidimensional figures that Keisha N. Blain explores in her new book Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom. In a remarkable act of historical recovery, Blain expertly traces the vital role women played in shaping black nationalist politics between the 1920s and 1960s. Challenging historical narratives that often emphasize the decline of black nationalism following the deportation of Marcus Garvey from the United States, she demonstrates how a diverse group of black women—operating in the US, the Caribbean, and Europe—worked to keep this political vision alive. Always attuned to the gender dynamics that shaped their politics, Blain has produced a landmark study that challenges us to think more deeply about black nationalism both as a political ideology and transnational activist program in the twentieth century.

Set the World on Fire is centered on a broad cast of historical actors, many of whom have been neglected by scholars and largely forgotten in popular memory. Expertly weaving together personal narratives with local, national, and global histories, Blain primarily focuses on Amy Ashwood Garvey, Amy Jacques Garvey, Ethel Collins, Maymie Leona Turpeau De Mena, Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, and Ethel Waddell. However, around every corner readers are introduced to new and often equally intriguing characters—particularly grassroots organizers, writers, and journalists—all of whom contributed to the development of black nationalist thought during this period. Indeed, the very title of the book is drawn from an article written by Josephine Moody, a Cleveland-based United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) member who, up until now, has been absent from the historical record.[1] The varied and diverse voices that animate the book are testament to Blain’s skill as a historian, as well as her diligent mining of neglected black nationalist publications, personal correspondence, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) files, and census records. These painstaking efforts to recover and do justice to the actions and ideas of these women provides vital historical context in terms of thinking about the range and dynamism of black nationalist organizing, while also providing a real sense of the forces, tensions, and ideologies that animated the movement. The book embeds these women’s lives as activists within the longer history of black nationalism, while also tracing how the Great Depression, New Deal, Second World War, and anticolonial movements around the world influenced their global outlook. This makes Set the World on Fire a clear and eminently readable book, ensuring that it will be accessible to broader public audiences at the same time as it breaks new scholarly ground. For me though, Set the World on Fire is particularly invaluable for the insights it offers on the gendered politics of black nationalism/internationalism, as well as the chronology and character of black resistance in the first half of the twentieth century.

Building on work by Barbara Bair, Ula Yvette Taylor, and others, Blain documents how women simultaneously embraced and subverted masculinist articulations of black nationalism.[2] While these activists often endorsed black male authority, they continued to insist that their central position at the heart of the black family and community entitled them to a public political platform. Throughout the book, Blain refers to this stance as a form of “proto-feminism,” which “challenged sexism and sought to empower black women globally but walked a fine line between advancing women’s opportunities and simultaneously supporting black men’s leadership” (p. 142).

This is perhaps most thoroughly explored in chapter 1, which examines the role of women within the UNIA. Blain documents the crucial role that Marcus Garvey’s two wives, Amy Ashwood and Amy Jacques, played in the practical and ideological development of the organization. She also demonstrates the key leadership contributions of Henrietta Vinton Davis, Mayme De Mena, Irene M. Blackstone, Ethel Maude Collins, Adelaide Casely Hayford, and Laura Adoker Kofey. These individuals forged prominent roles for themselves within the Garvey movement at various times, and in the process, were at the forefront of forging black nationalist networks throughout the Atlantic world. While aspects of this story have been told before, Set the World on Fire moves beyond existing scholarship that explores the gender politics of Garveyism by tracing how these formative experiences continued to shape black nationalist politics beyond the 1920s, long after the fragmentation of the UNIA. As Blain argues, “black women found a sense of empowerment in the UNIA, and the organization functioned as a political incubator in which many black women became politicized and trained for future leadership” (p. 20). While many women were influenced by Marcus Garvey’s Pan-African vision, they did not simply take his ideas forward unchanged. Instead they developed their own structures and initiatives that dramatically expanded black nationalism in subsequent decades. As Blain states in her introduction: “The black nationalist women chronicled in this book created spaces of their own in which to experiment with various strategies and ideologies” (p. 2).

In extending the chronology of black nationalism, Set the World on Fire also makes a valuable contribution to how historians think about and represent resistance. Shunning narrow questions concerning success/failure, the book instead documents how activist networks were forged and maintained, as well as how ideas spanned generations and national borders. The ways in which black women engaged with grassroots organizing, theorized black nationalism in print, and established strategic/pragmatic alliances all appear as central parts of this story.

The skill and persistence of black nationalist women as grassroots activists is apparent throughout the text. The organizational life of PME provides a telling example of this. Founded by former UNIA member Gordon in Chicago in 1932, the organization attracted an estimated three hundred thousand predominantly working-class supporters around the country, while PME activists (including Allen) traveled to the Jim Crow South working to recruit sharecroppers and tenant farmers to the black nationalist cause. As Blain summarizes, “During this era of global economic instability and political turmoil a large segment of the black working class in the United States embraced black nationalism—especially the core tenets of black capitalism, political self-determination, and emigration—as viable solutions to achieve universal black liberation” (pp. 48-49). The extent to which groups like the PME fostered a global political vision among the working class is particularly significant, providing a timely reminder that the politics of black internationalism resonated with everyday working people as well as prominent “race leaders.”

Black nationalist women also collectively resisted global white supremacy in print. Writing from the US, the Caribbean, and Europe, such figures as Ashwood Garvey, Jacques Garvey, Collins, Amy Bailey, and Una Marson used their journalism and creative writing to set out a political vision that would unite African people throughout the diaspora. Promoting Pan-African unity as a powerful response to European colonialism, these women once again insisted that the struggle against white supremacy needed to be global in scope. This is particularly apparent in chapter 5, where Blain outlines how black women fostered race pride and imaginatively constructed a shared race consciousness across national borders. As Jacques Garvey wrote in the Universal Ethiopian Students Association’s (UESA) newspaper The African, “the ties of blood that bind us transcends all national boundaries. The differences of languages and dialects are being overcome as all of us are learning the language of freedom” (p. 162). In this regard, Set the World on Fire joins a growing number of important works that examine the gender politics of black diaspora and the role that women played in mobilizing people of African descent in the struggle against global white supremacy.[3]

Finally, it is impossible to read this book and not to be struck by the resourcefulness and pragmatism of black nationalist organizers. Blain details how women lobbied for African emigration throughout the 1920s-50s, organizing petitions, writing editorials, delivering speeches, and supporting legislation—most notably, Senator Bilbo’s Greater Liberia Bill in the late 1930s that asked for federal funding to relocate African Americans to Liberia. Positioning this activism within the longer history of black emigration initiatives of Henry McNeal Turner and others in the nineteenth century, it is clear that the call to return to Africa continued to offer an appealing alternative to the violent forms of colonial and white supremacist power for people of African descent well into the twentieth century.

The efforts of Gordon, Allen, Jacques Garvey, and others to keep their African dreams alive further illuminate the pressures, strains, compromises, and negotiations that are central to understanding the black freedom struggle. Indeed, the strategic alliances that black nationalist women established with Senator Bilbo and other prominent white supremacists, such as Ernest Sevier Cox, that are explored in the text might initially appear to be reactionary and ultimately misguided. However, as Blain makes clear, black nationalist women always viewed these alliances as “a means to an end” (p. 119). As Gordon privately commented to a fellow PME organizer who had reservations about working with the senator from Mississippi: “When we have to depend on the crocodile to cross the stream … we must pat him on the back until we get to the other side” (p. 124). Black nationalist women were acutely aware of the scale of the task they faced and worked to harness every resource they possibly could to achieve the right to self-determination.

This is not to say that the tensions and shortcomings of black nationalist politics are overlooked in the book. Blain is particularly critical of the “civilizationist” outlook of many of the women featured in her study, who often advanced narratives of African primitivism and assumed that it was the duty of the “New Negro” in the US, the Caribbean, and Europe to uplift their brothers and sisters on the other side of the Atlantic. While pride in one’s heritage and the celebration of ancient African civilizations were certainly key features of black nationalist thought, many activists continued to buy into colonial narratives about the supposed backwardness of the “Dark Continent.” As I was reading these sections, I found myself thinking what Africans themselves thought of these black nationalist efforts. African connections feature throughout this study, as we learn about how Hayford spread Garveyism in Sierra Leone, how PME delegations traveled to Liberia, and what role African activists played in shaping Ashwood’s black nationalism in London and in Africa. However, I was still left wondering about the extent to which African anticolonial leaders were able to engage with the global outlook of black nationalist women? Did they challenge or correct their civilizationist language, for example? While this is beyond the scope of what is already an incredibly broad and impressive study, these questions perhaps remind us of the continued need to bring more African voices and perspectives into histories of black internationalism.

Ultimately, Set the World on Fire represents a landmark intervention in the thriving field of black international history. Indeed, more broadly, I would argue that it essential reading to anyone wanting to better understand the history of race, empire, and imperialism in the twentieth century. Perhaps most important though, Blain provides us with a timely reminder of the militancy and tenacity of the women who were at the heart of black nationalist politics. While they would not live to see the realization of their political visions, these women created the ideological and practical tools for future generations of activists to take up the global struggle against white supremacy.

Piece originally published at H-Net under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License.

Notes

[1]. Josephine Moody, “We Want to Set the World on Fire,” New Negro World, January 1942.

[2]. Barbara Bair, “True Women, Real Men: Gender Ideology and Social Roles in the Garvey Movement,” in Gendered Domains: Rethinking Public and Private in Women’s History: Essays from the Seventh Berkshire Conference on the History of Women, ed. Dorothy O. Helly and Susan Reverby (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1992); Ula Yvette Taylor, The Veiled Garvey: The Life and Times of Amy Jacques Garvey (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002); and Asia Leeds, “Toward the ‘Higher Type of Womanhood’: The Gendered Contours of Garveyism and the Making of Redemptive Geographies in Costa Rica, 1922-1941,” Palimpsest: A Journal on Women, Gender, and the Black International 2, no. 1 (2013): 1-27.

[3]. For recent landmark studies in this field, see Carole Boyce Davies, Left of Karl Marx: The Political Life of Black Communist Claudia Jones(Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008); Ashley D. Farmer, Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017); Dayo F. Gore, Radicalism at the Crossroads: African American Women Activists in the Cold War, repr. ed. (New York: New York University Press, 2012); Cheryl Higashida, Black Internationalist Feminism: Women Writers of the Black Left, 1945-1995 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013); Erik S. McDuffie, Sojourning for Freedom: Black Women, American Communism, and the Making of Black Left Feminism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); Imaobong D. Umoren, Race Women Internationalists: Activist-Intellectuals and Global Freedom Struggles (Oakland: University of California Press, 2018); Tracy Denean Sharpley-Whiting, Bricktop’s Paris: African American Women in Paris between the Two World Wars (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2015); and Bianca C. Williams, The Pursuit of Happiness: Black Women, Diasporic Dreams, and the Politics of Emotional Transnationalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018).