The ‘Female Byron’

The celebrity poet Letitia Elizabeth Landon mesmerized a 19th-century public with hints of dark secrets.

The story ended in October 1838 in modern-day Ghana, at Cape Coast Castle, a British commercial garrison and a former slave-trading post. There, the recently married 36-year-old wife of the chief British official, George Maclean, was found by her maid dead on the floor of her dressing room, an empty prescription bottle of highly toxic prussic acid in her hand. Nearby, probably in Accra, were the governor’s “country wife” and her several children; upon the new wife’s arrival from the literary precincts of London, they had been discreetly removed from the castle. Rumors would soon circulate in Britain that the governor’s previous consort was the murderer, though no evidence emerged to support those suspicions. On the desk was an unsent letter, banal and cheerful, rather than a suicide note.

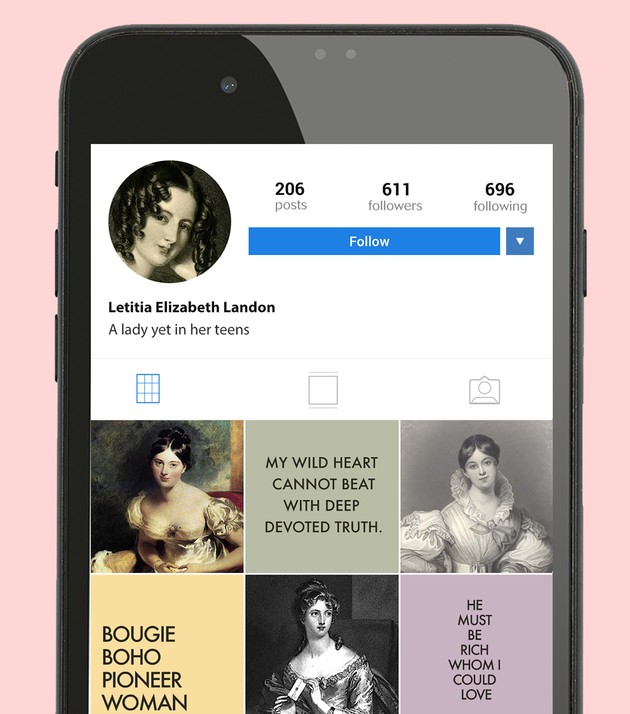

The enigmatic celebrity death was of a piece with the life. Under the pen name “L.E.L.,” Letitia Elizabeth Landon had been one of the most famous literary women of her brief pre-Victorian moment, her poetry a staple of the popular literary press for well over a decade. A child of bourgeois-bohemian London, she had earned fame early on for her canny way of promising confessions that never quite materialized, lamenting all that she could not tell. She was a performer whose alluring mystery—constant hints and half-revelations—was her calling card. Was she the lovelorn maiden, virginal and yearning? The betrayed woman, experienced too soon? Was she sinner, victim, or the cynic playing at both poses? Even her several portraits look like different women.

L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated “Female Byron” is the first biography of Landon to explore recent revelations about her life, and the literary critic Lucasta Miller’s sleuthing delivers an unexpected result. The figure who emerges from her pages is not just a missing link in literary Romanticism, but a progenitor of something modern: Landon explored the art of performative self-creation in the commercial press—an art fated to become a habit in the social-media age—and she was one of the first to pay its costs. Neither sincere in a 19th-century sense nor confessional in a 20th-century one, L.E.L.’s signature style was a curiously opaque self-obsession.

She took the suffering of love as her consistent theme, but wrote with fluctuating tones. One note was the genuineness of her longing:

Oh! say not, that for me more meet

The revelry of youth;

Or that my wild heart cannot beat

With deep devoted truth.

Yet this could be followed by:

He must be rich whom I could love,

His fortune clear must be,

Whether in land or in the funds,

’Tis all the same to me.

These verses were published in the same magazine on the same day in 1821, when she was 19. From the start, L.E.L. projected a public form of femininity by combining bold directness with a strange detachment. Intimations of some dark experience lurked in her verse. She seemed to crave public exposure and yet remained a cipher; hers was a voice seeking to escape the claustrophobia of solitude, yet prone to the agoraphobia that came of total visibility. No core self ever came into focus.

This was a mode of public personality inseparable from the commercial audience that consumed it, and the interest of Miller’s biography lies in watching a new form of self-presentation being invented by an unheralded young woman. The story Miller tells suggests that this mutable identity, scripted for mass consumption, was at its origin bound up with female experience: Its impetus, in L.E.L.’s pioneering case, was a distinctively female secret, one that we can now join a small group of Landon’s initial readers in knowing.

Starting in 1820, Landon’s poetry appeared in The Literary Gazette, one of a new kind of magazine that emerged in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars. Less overtly political than their predecessors, these publications flaunted their voguish instincts and aimed at mass readership. They adopted a self-referential stance of discussing the very notoriety they spread; they offered an insider’s guide to what we might now call celebrity culture and its secrets, in a lightly mocking tone that hailed literary, theatrical, and political notables with one hand while knocking them down with the other.

L.E.L.—revealed by an early editor’s note to be “a lady yet in her teens”—presented an especially fascinating mystery: How could a young female adopt, with a precocious knowingness, the erotic pessimism of late Romantics such as Byron, on display in verses like these of 1823?

Twine not those red roses for me,—

Darker and sadder my wreath must be;

Mine is of flowers unkissed by the sun,

Flowers which died as the Spring begun.

The blighted leaf and the cankered stem

Are what should form my diadem.

A voice like this invited both heartfelt identification and prurient attention. For readers of one kind (generally speaking, female and provincial), it conveyed the drama of an inner life stifled by a lack of expressive outlets. Charlotte and Emily Brontë, in their adolescence, were two such readers. Other readers (male, metropolitan) heard in the voice a code and a come-on, the sly declarations of someone they might meet, seduce, capture. If the poet had mysteries, they could learn them; desires, they could satisfy them. Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the future novelist, politician, colonial administrator, and peer, was one of these. He later remembered the craze of speculation that L.E.L. inspired: “Was she young? Was she pretty? and—for there were some embryo fortune-hunters among us—was she rich?”

Bulwer-Lytton, as it happened, ended up in Landon’s milieu and learned what would remain publicly unknown for generations to come: When the 20-year-old Landon wrote those lines in the spring of 1823—her bankrupt father having absconded and her family facing poverty—she was pregnant by The Literary Gazette’s married editor, William Jerdan, who had offered a financial lifeline by agreeing to publish her. That secret was rediscovered in 2000, when an American doctoral student named Cynthia Lawford revealed proof that Landon had given birth to three children by Jerdan in the 1820s. The children had been given up, and went on to lead lives of varying degrees of obscurity in Australia, Trinidad, and Britain. This was the shame the poetry hinted at.

The predatory Jerdan—Miller asserts that he fathered 23 children by multiple women—had tired of Landon by the early 1830s. But he did so only after having acted as her banker as well as her editor, appropriating much of her earnings in futile attempts to secure for himself an upper-bourgeois foothold. He may even have leveraged Landon’s secret: Henry Colburn, Jerdan’s creditor and also one of the Gazette’s owners, published in 1826 clever allusions to Landon’s pregnancies in other papers he owned, stoking the gossip around which her poetry delicately maneuvered. L.E.L. was a property, and making that property pay depended on careful manipulation of her hidden life.

Continually hard up, Landon tried every kind of commercial literary venture: not just poetry for magazines, but large amounts of verse for the newly popular “annuals”—luxe, kitschy illustrated gift books, such as one called Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrap Book. She even wrote “silver fork” novels about high-society life, such as 1831’s Romance and Reality, a melodrama of hopeless love that leads her young female protagonist from London drawing rooms to a Neapolitan convent and then to an early death. Landon’s own health was poor, and her world was small by necessity. Her doctor, for instance, was the Gazette’s medical columnist, an arrangement Jerdan may have made to reward him for his discretion. As the new proprieties of the early Victorian period descended, the titillating knowledge of Landon’s private life turned to mockery and distaste in the very literary circles that had initially fostered her celebrity. Anonymous letters ended a brief 1835 engagement to the law student and literary aspirant John Forster. As Landon entered her 30s, the calculated ambiguity that had made her name now threatened to undo her.

Finally, when the outsider Maclean entered her orbit in 1836, a network of friends and wealthy acquaintances colluded to marry her off and remove her to Africa. Like everything else in Landon’s story, profit was a primary motive. In dangling her before Maclean as a prospective famous spouse, one pivotal intermediary sought to gain a key commercial contact. The marriage spelled escape, but also exile. When news of her death reached Britain (Miller suggests suicide, either intentional or subconscious), this mercenary attitude switched to remorse—which expressed itself in the connivance of her memoirists, Jerdan among them, to remain silent about her true story. The move served as both self-protection and expiation. Landon was retroactively sanitized, repackaged as a virginal victim of her heart’s unrequited yearning. So she remained through the 20th century: an emblem of the insipid, the merely girlish. The upshot was that she became all the more forgettable, and gradually forgotten.

Miller is a debunker by temperament, fascinated by the space between image and truth in cultural history. The Brontë Myth (2001) charted with pugnacious glee the distortions by which Charlotte and Emily were turned into saintly mystics. Here is a case tailor-made for her: a story of exploitation in which cultural operators conspire to foster, manipulate, and then callously snuff out an artistic talent, lying all the while. That L.E.L.’s chosen metaphors—enslavement to passion, the melancholic will to self-erasure—had a perverse way of becoming reality lends an added frisson. Landon died, after all, in a castle built above former slaveholding dungeons. Miller is unafraid of anachronisms and applies them vividly. Jerdan’s sinister “grooming” of Landon was ignored by her indebted family members, who in their haste to benefit from her talents were not overscrupulous in protecting her. Euphemisms such as protégée tell only part of the tale: Landon was “pushed onto the casting couch” and did what was required.

Miller delves eagerly into the menacing, male-dominated world of magazines and publishers—the rooms filled with cigar smoke and raucous jokes, the leering family men, the camaraderie built on roguish convenience or bribery, the brutally shifting fortunes of editors and writers alike. Compared with the anodyne picture of the culture industry in most scholarship, Miller’s portrait is detailed and tenaciously cynical—and truer. In her hands, Landon’s story is a recognizably modern tragedy, that of the female artist forced to earn attention by reshaping her exploitation into a febrile glamour, knowing all the while that eventually titillation will become condemnation.

Why attend to Landon’s life now, other than as yet another story about the depredations of men who hold the levers of cultural power? The interest Landon holds for us lies in the tenuous autonomy she constructed for herself while in the grip of that machinery. Always Landon seems to be asking, Why do I have this life? I didn’t choose it; it both is and isn’t my self. The result was a manner that played with multiple poses, particularly male ones, such as Byronic melancholy and Keatsian sensuality—but remained detached from all of them. The style could be clichéd, as with her frequently lovelorn persona, acknowledging both the truth and the trap of clichés. It was offhand and urgent, somehow haunting and disposable at the same time. She wrote as if every utterance were set to auto-delete. The effect was to privilege the halting, sloppy, and incomplete self. The voice was a desperate and brilliant compromise with a voracious and invasive commercial culture, and its strategy has endured.

This article appears in the April 2019 print edition with the headline “The Curated Self, Circa 1820.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.