Being Unique Is Overrated

Publicity portrait of Marilyn Monroe as Rose Loomis in Niagara, 1953

by Paul Vacca

What if the uniqueness so often praised in Art in our self-help books was just a delusion? A remnant of our crass romanticism? The proof is in the pudding with Warhol’s Shot Marilyn which sold for €195 million at Christie’s…

Being a unique piece of art seems to be a prerequisite for breaking the bank. If people come from all over the world to see the Mona Lisa, it is because there is only one. Just as Fontaine, Marcel Duchamp’s urinal, or White on White, Malevitch’s suprematist monochrome, are unique. Art — real art — is largely a matter of uniqueness, of ipseity; the rest is at best handicraft.

On Monday 9 May, 2022, at Christie’s in New York, an Andy Warhol painting of Marilyn Monroe was auctioned. The sales pitch spoke of a painting that “transcends the portrait genre, at the pinnacle of 20th century art” that deserves to stand “alongside Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, Vinci’s Mona Lisa and Picasso’s Maid of Avignon: one of the greatest paintings of all time.”

Nicely written: the perfect pitch for a painting that is not unique.

For it is not, strictly speaking, an original work, but the transfer of another work: the photo of Henry Hathaway — never credited by the Pope of Pop Art — for the promotion of the film Niagara, released in 1953. But Warhol had already accustomed us to this with Coca-Cola and Campbell Soup cans.

Above all, Warhol’s Marylin actually exists in 5 copies.

Yet the painting sold for $195 million, eclipsing the last record for an American artist (a Basquiat sold for $110.5 million in 2017): the highest price for a 20th century artist, ahead of Picasso and just behind Da Vinci.

But why on earth did a buyer shell out $195m for a painting that exists in five nearly identical copies? It’s crazy, of course. But it’s not absurd, either.

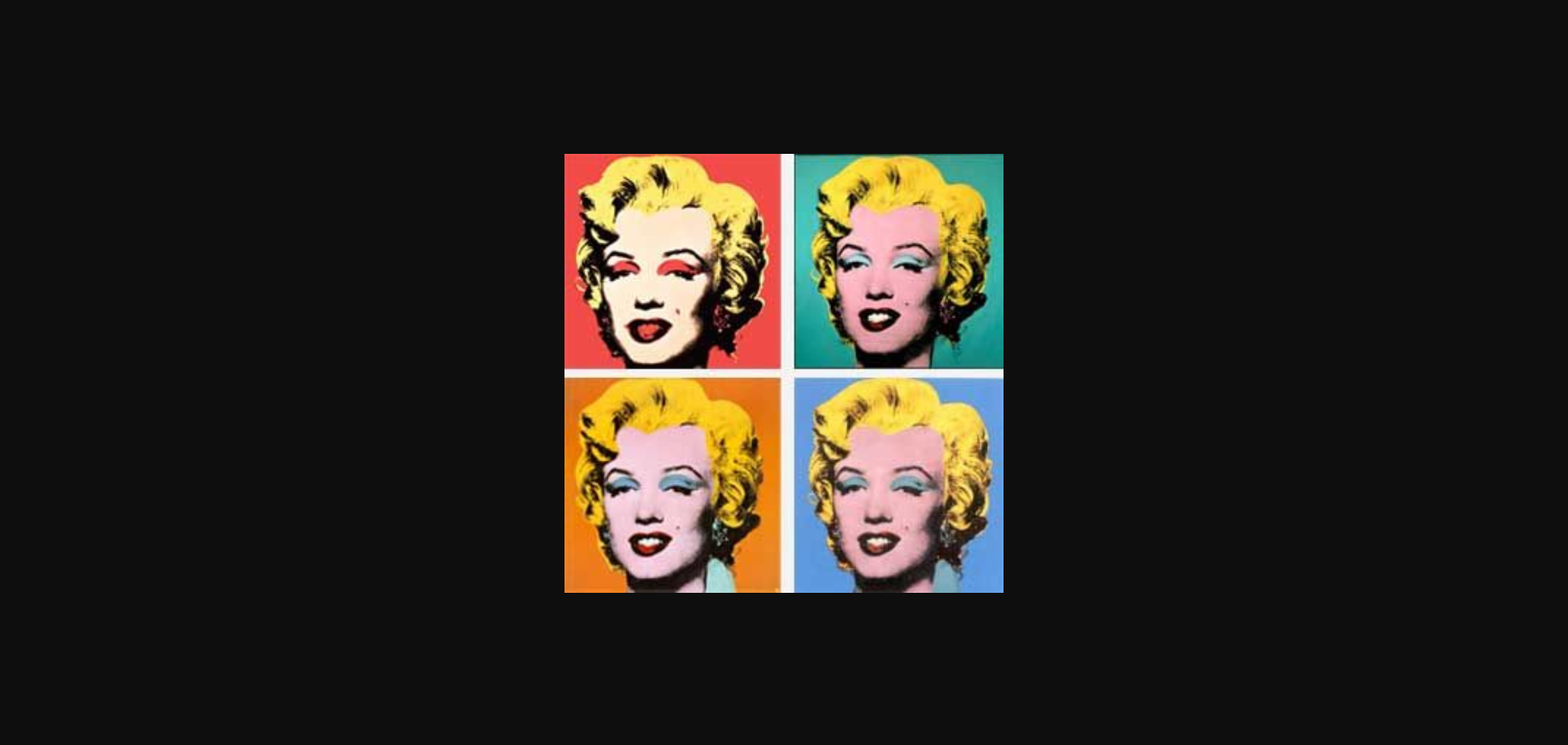

Andy Warhol, Shot Marilyns, 1964

Andy Warhol, Shot Marilyns, 1964

First, because this one metre by one metre square has a narrative. It belongs to the Shot Marilyn series, so called because the performer Dorothy Podber, invited to the Factory, saw the Marilyns and asked the master of the house: “Can I shoot them?” Warhol agreed, misunderstanding the meaning of the performer’s request who took out not a camera but a gun and put a bullet in Marilyn’s temple, passing through all four canvases. (Warhol later repaired the damage).

Second, because compared to other Warhol silkscreens — such as the 250 Mao prints — this one is all in all relatively rare.

Third, because this piece has a first-rate pedigree, having passed through the hands of the greatest collectors, sold at the time by Leo Castelli, the New York gallery owner, which gives it an exceptional, aristocratic lineage.

Finally, and above all, because acquiring a work that is not unique has financial advantages. Isn’t it safer than buying a Salvator Mundi for $450 million, which is certainly unique, but we don’t even know if it’s an authentic Vinci?

Warhol not only understood the mechanisms of celebrity, but also suspected the mechanisms of reassurance in the art market. To buy a unique work is to be alone and to expose oneself to risk. A problem well known to real estate people: an unclassifiable product is often unmarketable.

Buying a piece of art on the market is not just about owning the work: it is an invaluable pass to the community of wealthy aesthetes who gather at contemporary art fairs and auction houses in Basel, New York, Miami or Hong Kong.

So it doesn’t matter whether it’s unique or not (as long as it is not a fake). Because if luxury is inspired by art, the reverse is also true: buying a work of art today, like purchasing a luxury product — a bag, a watch or a yacht — is above all belonging to a club. Between the two, there is sometimes only a simple difference of zeros.

But what if, in the end, it was uniqueness that was overpriced? Is it not just a bubble? A mere figment of the imagination? A remnant of our crass romanticism? Because, in the end, there is nothing exceptional about being unique: everything is unique and nothing is. Ah, the uniqueness that we sell and that we praise at every turn, even in our personal development books or in our LinkedIn statuses!

“Nothing is so unique that it cannot be included in a list”, remarked Georges Perec, the Oulipo’s founder author of A Void. If only in the list of things that boast their uniqueness.

Note

This column is not unique either: a first version has already been published in French in Trends-Tendances magazine on 11 May 2022.

About the Author

Paul Vacca is a novelist, essayist and speaker. He gives courses and lectures at the Institut Français de la Mode (IFM Paris), Technocité (Brussels) and collaborates with the think-tank Volta (Milan). He writes a weekly column for the Belgian magazine Trends-Tendances and for the French magazine Ernest. He is the author of 4 novels and 5 essays. His first novel La Petite Cloche au son grêle (Mum, Marcel Proust and Me) published in paperback at Le Livre de Poche in 2013 have met a great success and was translated in Japan, and won several prizes (Madeleine d’Or Marcel Proust 2009 – Laureate of the First Novel Festival of Chambery, Laval and Mouscron…). Recently published, two literary essays Michel Houellebecq, phénomène littéraire published by Robert Laffont (2019) and Les vertus de la bêtise (“On Stupidity – And How It Can Make Us Smarter”) by the Editions de l’Observatoire (2020). He is currently working on the adaptation of his latest novel Au jour le jour (“The Feuilletonist”) for the screen.

Image Rights

Monroe’s publicity portrait is in the public domain. Warhol’s art is reproduced here in low-resolution under fair use.