The Gossip Trap

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Dutch Proverbs, 1559 (detail)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Dutch Proverbs, 1559 (detail)

by Erik Hoel

On Rousseau, Essay Contests, Political Motivations for Revisiting the Origin of Human Civilization, and the Book Is Introduced

In 1754 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, at the comfortable age of 42, was composing a monograph for an essay contest not dissimilar to this one. Hosted by a local university, the prompt for the contest was “What is the origin of inequality among people, and is it authorized by natural law?” Rousseau’s submission, Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men, became an intellectual sensation. In its long life as one of the foundational documents of the Western world it has been, at times, blamed for the bloody slaughter of The Terror, and, at other times, lauded as the inventor of the progressive Left.

Disqualified from winning the contest due to its unapologetic length, the Discourse’s depiction of an original state of nature populated by noble savages, a state eventually sundered by agriculture and the invention of private property, was monumentally influential. His genius move was to politicize the past, offering up an alternative mirror to Hobbes’ view, itself already political, which portrayed life in prehistorical societies with that oft-repeated phrase: “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Hobbes, founder of the political Right, and Rousseau, founder of the political Left, both built their arguments on the bedrock of prehistory. But on different bedrocks. The lesson being: if you want to change human society, change the past first.

Enter The Dawn of Everything, which tries to change the past by taking a third way orthogonal to the Rousseau/Hobbes spectrum. Published to widespread acclaim last year, it was blurbed by the likes of Noam Chomsky and Nassim Taleb, and given glowing reviews in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and many others. A doorstopping tome of public-facing but dense scholarship, it harkens back to back to an older age—it even has overwrought Victorian section titles calligraphed in ALL CAPS.

It’s a co-authored book by David Graeber and David Wengrow. The Davids. First, we have David Graeber, anthropologist, famed author of Debt: the First 5,000 Years, notable figure in the 2011 Occupy Wall Street movement, a playful but snarky writer, almost certainly the reason for the section titles being the way they are, and now deceased at the relatively young age of 59, dying just several weeks before The Dawn of Everything was published, victim of a totally inexplicable and blazingly fast case of necrotizing pancreatitis. The surviving David, David Wengrow, is lesser known but more erudite, more pragmatic, classically academic both in his pedantry but also in his impressive armament of archeological knowledge, and it’s Wengrow who’s been trying to fill the shoes of the more famous Graeber by making the post-publishing media whirlwind tour, sometimes to visible discomfort as he goes on long-winded lectures while the hosts try hastily to cut to the next segment.

What is the version of prehistory the Davids offer in The Dawn of Everything? It is an anti-story. The Davids are offering up an alternative to (as well as a criticism of) thinkers like Steven Pinker or Jared Diamond or Yuval Noah Harari, all of whom give a standard model of human prehistory that goes small hunter-gatherer tribes → invention of agriculture → civilization (with its associated hierarchies and private property and wealth inequalities).

The original hunter-gatherer tribes are often reasoned about via the analogy of contemporary hunter-gatherer tribes (or at least, those in recent history surveyed by anthropologists). Yet which tribe is an “appropriate” analogy changes depending whether the reasoner is a follower of Hobbes or Rousseau; a modern Hobbesian might prefer to use the war-like Yanomami as the analogy, whereas a follower of Rousseau might prefer the more peaceful and egalitarian Hadza, Pygmies, or !Kung.

The thesis of The Dawn of Everything is that neither of these is correct. In fact, the Davids argue the standard model of prehistory isn’t supported at all by modern archeological and anthropological evidence; in its place they offer a complexified account, wherein prehistorical humans lived in a panoply of different political arrangements, from extreme egalitarianism to chattel slavery, and that, just like humans in recorded history, they consciously collectively chose to live in the arrangement they did (well, except for the slaves), with the result being that

the world of hunter-gatherers as it existed before the coming of agriculture was one of bold social experiments, resembling a carnival parade of political forms. . . Agriculture, in turn, did not mean the inception of private property, nor did it mark an irreversible step towards inequality. In fact, many of the first farming communities were relatively free of ranks or hierarchies. And far from setting class differences in stone, a surprising number of the world’s earliest cities were organized on robustly egalitarian lines. . .

So for the Davids, the question is not, as it was for Rousseau, “How did inequality arise?” but rather, given the diversity of prehistorical ways of life, “How did we get stuck with the inequalities we have?”

This is a very interesting question to ask and the Davids marshal a veritable trove of evidence, some of which really does convincingly support their theses. But there is a problem with the book. For their own version of prehistory is corrupted by politics, the same corruption they accuse Rousseau and Hobbes and other thinkers of falling prey to before them. After all, the Davids’ express purpose is to argue that humans, in their diverse forms of prehistorical governments, are free, even playful, and capable of imagining new ways of living and consciously choosing to live in these ways, which the authors take to imply that their own beliefs in radical progressivism, or post-capitalism, might therefore be successful in our modern world—and moreso, that their research implies our current world and its ills are, in turn, a choice. The Davids certainly don’t hide their political goals, either in the book or in interviews, and their leanings are evident from the way it’s written as well: their eagerness to line up with progressivism spins throughout like a finely-tuned gyroscope. The result is a tendency to get carried away and issue blanket statements, like how Western civilization is currently great “except if you’re Black,” or outright misrepresentations of their intellectual opponents, like assigning to Steven Pinker the claim that “all significant forms of human progress before the twentieth-century can be attributed only to that one group of humans who used to refer to themselves as ‘the white race’” (Pinker doesn’t claim this), or rejecting the science of kinship-based theories of altruism with reasoning like “many humans just don’t like their families very much” (these are all real quotes).

Somewhere, within the morass of innuendo and expressions of their own political leanings, as well as the undeniable encyclopedic display of archeological and anthropological knowledge, there is a truth as to how humans lived prehistorically, and how civilization, with all its ills (and its goods) came to be. But what is that truth?

The Agriculture Revolution Was No Revolution, Nor Did it Inexorably Lead to Inequality; Inequality, Even Chattel Slavery, Already Existed

Our world as it existed just before the dawn of agriculture was anything but a world of roving hunter-gatherer bands. It was marked, in many places, by sedentary villages and towns, some by then already ancient, as well as monumental sanctuaries and stockpiled wealth. . .

And with this the Davids begin their dissection of the idea that agriculture was the root cause of political inequality, arguing that agriculture was not actually a “revolution” that irrevocably changed how humans lived.

Instead, the Davids present a wave of evidence that pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer societies could be incredibly politically diverse, and, sometimes, rival the worst atrocities of modern societies; at other times, they could rival their best. They zoom into the Native American foragers (not farmers) who lived on the California coastline, and observe substantial political differentiation, even out thousands of years into the past. Particularly between the Yurok in California and their northern neighbors of the Northwest Coast. The Yurok

struck outsiders as puritanical in a literal sense. . . ambitious Yurok men were ‘exhorted to abstain from any kind of indulgence. . . Repasts were kept bland and spartan, decoration simple, dancing modest and restrained. There were no inherited ranks or titles.

Compare that to the Native Americans of the Northwest Coast, right above them:

Northwest Coast societies, in contrast, became notorious among outside observers for the delight they took in displays of excess. . . They became famous for the exuberant ornamentation of their art.

The Yurok and other micro-nations to the south only rarely practiced chattel slavery. In stark contrast,

in any true Northwest Coast settlement hereditary slaves might have constituted up to a quarter of the population. These figures are striking. As we noted earlier, they rival the demographic balance in the colonial South at the height of the cotton boom and are in line with estimates for household slavery in classical Athens.

Indeed, there is evidence of Native American chattel slavery that goes back to 1850 BC in Northwest Coast societies (again, these are not agricultural societies).

The behavior of the Northwest Coast aristocrats resembles that of Mafia dons, with their strict codes of honour and patronage relationships; or what sociologists refer to as ‘court societies’—the sort of arrangement one might expect in, say, feudal Sicily. . .

So we have slave-owning Mafia dons to the north, and meanwhile, ascetics to the south. Despite both being foragers, they ate extremely different diets, with Californian tribes relying on nuts and acorns, while the Northwest Coast societies were sometimes referred to as ‘fisher-kings’ (presumably due to their two loves: aristocracy and fish). As the Davids say,

this is emphatically not what we are taught to expect among foragers. . . within the tiny communities that did exist, entirely different principles of social life applied.

Furthermore, the Davids make a good case that agriculture was not the sort of parasitic memetic invasion it is often portrayed as by writers like Yuval Noah Harari.

Once cultivation became widespread in Neolithic societies, we might expect to find evidence of a relatively quick or at least continuous transition from wild to domestic forms of cereals. . . but this is not at all what the results of archeological science show.

Instead

the process of plant domestication in the Fertile Crescent was not fully completed until much later: as much as 3,000 years after the cultivation of wild cereals first began (. . . to get a sense of the scale here, think: the time between the putative Trojan War and today).

This is despite the fact that scientific experiments on wheat genetics have revealed that

the key genetic mutation leading to crop domestication could be achieved in as little as twenty to thirty years, or at most 200 years, using simple harvesting techniques like reaping with flint sickles or uprooting by hands. All it would have taken, then, is for humans to follow the cues provided by the crops themselves.

So if it was a revolution, it was one that occurred as slowly as almost all of post-literate human history combined. And not only that, but prehistorical societies seem to occasionally develop agriculture and then consciously abandon it, preferring some other way of life. The Davids give several examples of this, including the builders of Stonehenge, who

were not farmers, or at least, not in the usual sense. They had once been; but the practice of erecting and dismantling grand monuments coincides with a period when the people of Britain, having adopted the Neolithic farming economy from continental Europe, appear to have turned their backs on at least one crucial aspect of it: abandoning the cultivation of cereals and returning, from around 3,300 BC, to the collection of hazelnuts as their staple source of plant food. . .

This sort of laissez-faire attitude toward farming is true in many other places, for example, in the early Amazonia there are seasonal cycles in and out of farming, and same for the habit of keeping pets but not domesticating animals fully, i.e., people who were neither forager or farmer, and often for thousands of years.

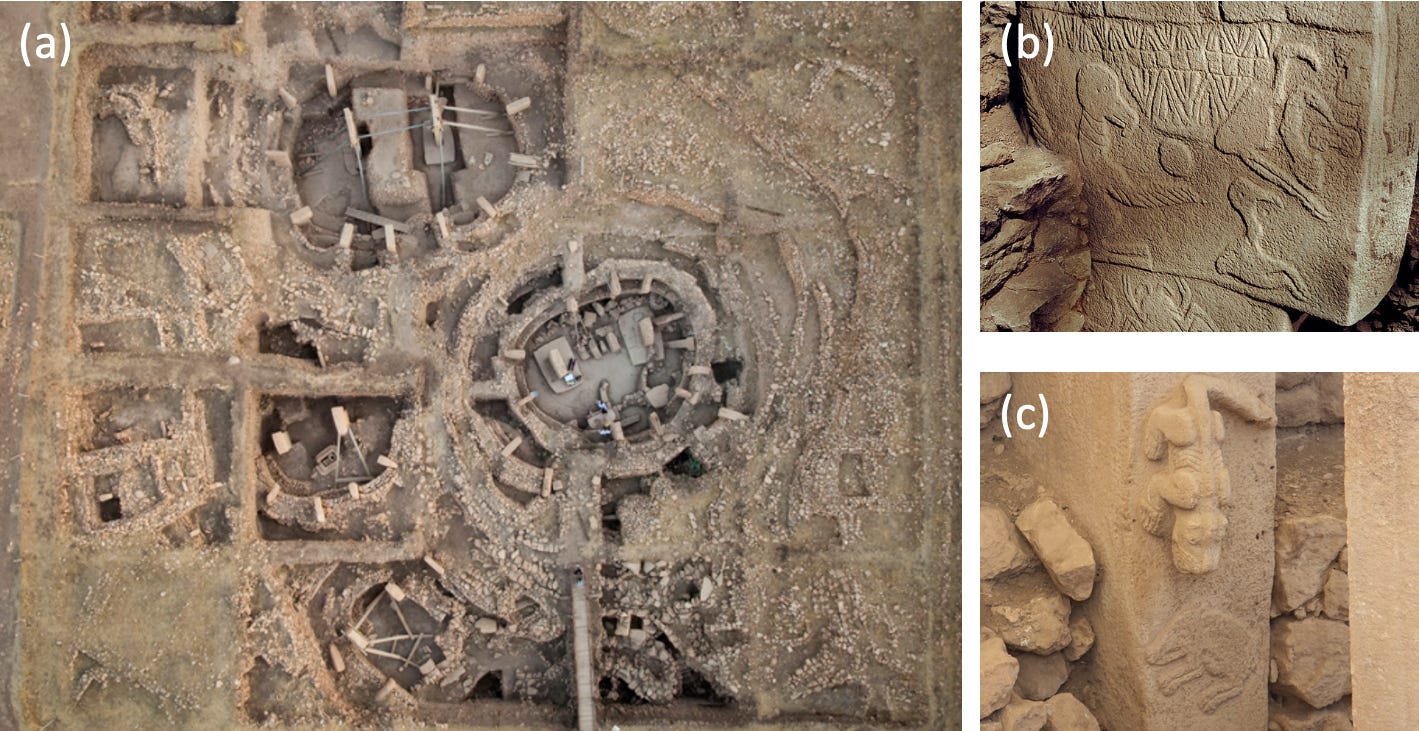

Nor did the agricultural revolution, even as it was occurring, result in one way of living; it seems like during the transition toward farming very different societies were possible, even those that lived in proximity to one another, the exact same as hunter-gatherer societies. Consider the upland and lowland sectors of the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East; sectors which are themselves demarcated by Göbekli Tepe, the world’s oldest construction of stone megaliths, dated to around 9,000 BC.

Between the upland and lowland sectors we see, again, political differentiation. North of Göbekli Tepe, in the upland, there was a city wherein at

the centre of the settlement stood a long-lived structure that archeologists call the ‘House of Skulls’, for the simple reason that it was found to hold the remains of over 450 people, including headless corpses and over ninety crania, all crammed into small compartments. . . Human remains in the House of Skulls were stored together with those of large prey animals, and a wild cattle skull was mounted on an outside wall. . . Studies of blood residues from the surface, and from associated objects, led researchers to identify this as an altar on which public sacrifice and processing of bodies took place, the victims both animal and human.

In comparison, lowland villages of the Fertile Crescent also attached a great importance to human heads, but treat them in an altogether different manner, in a way one might describe as touching (despite its macabre nature), like the ‘skull portraits’ found in lowland Early Neolithic villages.

These are heads that are removed from burials of women, men, and occasionally children in a secondary process, after the corpse had decomposed. Once separated from the body, they were cleaned and carefully modelled over with clay, then coated with layers of plaster to become something altogether different. Shells were often fixed into the eye sockets, just as clay and plaster filled in for the flesh and skin. Red and white paint added further life. Skull portraits appeared to be treasured heirlooms, carefully stored and repaired over generations. They reached the height of their popularity in the eighth millennium BC. . . one such modelled head was found in an intimate situation, clutched to the chest of a female burial.

Such details in art and priorities corresponded to political differences: the upland sectors of the Fertile Crescent were

most clearly distinguished by the building of grand monuments in stone, and by a symbolism of male virility and predation. . . By contrast, the art and ritual of the lowland settlements in the Euphrates and Jordan valleys presents women as co-creators of a distinct form of society—learned through the productive routines of cultivation, herding and village life—and celebrated by modelling and binding soft materials, such as clay or fibres, into symbolic forms.

And yet we know that the regions traded with one another. There are plenty of other examples of political differentiation, both pre- and post-agriculture, although even the Davids are forced to admit that agriculture marks a change. Eventually it

saw the creation of patterns of life and ritual that remain doggedly with us millennia later, and have since become fixtures of social existence among a broad sector of humanity: everything from harvest festivals to habits of sitting on benches, putting cheese on bread, entering and exiting via doorways, or looking at the world through windows.

But the fact that humans were able to invent, and then abandon, agriculture, and have inequality or equality to greater degrees throughout the invention of agriculture, and to continue to have political differentiation after agriculture, all suggests to the Davids that our ancestors, despite (as one might say) having the handicap of living in prehistory, were choosing to live a certain way, not simply driven like automaton by environmental inputs or new inventions. They made conscious political choices, just like us.

Conscious Political Choice Among Native Americans and the “Indigenous Critique” of Western Civilization

This thesis may sound surprising, but the Davids bemoan that this is because non-Western, non-European civilizations are consistently stripped of political self-consciousness in standard historical accounts, e.g.,

to Victorian intellectuals, the notion of people self-consciously imagining a social order more to their liking and then trying to bring it into being was simply not applicable before the modern age. . . this would have come as a great surprise to Kandiaronk, the seventeenth-century Wendat philosopher-statesman. . . Like many North American peoples of his time, Kandiaronk’s Wendat nation saw their society as a confederation created by conscious agreement; agreements open to continual renegotiation.

The conversational nature of the Wendat government led most Jesuits to describe French-speaking Native Americans as highly eloquent, as, at least among those who spoke Iroquoian languages, open conversation and debate were how tribe decisions got made, a process that rewarded the more eloquent and convincing of its members (although not all Native American states valued the reasonable debate of the Iroquois).

But somehow the self-consciously political nature of New France was replaced by either the idealized fantasies of Rousseau or the idealized barbarism of Hobbes. The Davids have a story for how that happened, and it actually involves Kandiaronk himself. They argue that Native American intellectuals were the true originators of many of the criticisms of the Western World that would go on to define the political Left, and European intellectuals in turn co-opted their criticisms, using fictional Native Americans as mouthpieces, while the originals were forgotten to mainstream history. This is because Native American intellectuals,

when they appear in European accounts, are assumed to be mere representatives of some Western archetype of the ‘noble savage’ or sock-puppets, used as plausible alibis to an author who might otherwise get into trouble for presenting subversive ideas. . .

The reality was quite different, the Davids suggest, once you investigate evidence from the Great Lakes region where tribes like the Wendat, and Jesuits and fur traders, all mixed together. In the late 1600s, Lahontan, a French aristocrat, spent much time in New France, and there met the Kandiaronk (also called ‘Le Rat’, since his name meant ‘muskrat’). Kandiaronk was

at the time engaged in a complex geopolitical game, trying to play the English, French, and Five Nations of the Haudenosaunee off against each other. . . with the long-term goal of creating a comprehensive indigenous alliance to hold off the settler advance. . . Everyone who met him, friend or foe, admitted he was a truly remarkable individual: a courageous warrior, brilliant orator, and unusually skillful politician.

Kandiaronk was known for engaging the Europeans in debate, attending their dinner parties to converse with them, and Lahontan witnessed some of these debates and knew Kandiaronk personally. Later, an old man in Europe, Lahontan would publish Curious Dialogues with a Savage of Good Sense Who has Traveled which was a dialogue between fictional versions of himself and Kandiaronk; the latter offered forth convincing and eloquent critiques of European civilization, from its pitilessness to those in need, to its obsession with money, to its social inequality, to its lack of basic human freedoms that the Wendat still possessed. This “indigenous critique”

won a wide audience, and before long Lahontan had become something of a minor celebrity. He settled at the court of Hanover, which was also the home base for Leibniz, who befriended and supported him. . .

The indigenous critique served as a shock to the European system, setting the path to Rousseau’s Discourses by creating an entire genre of literature, as

just about every major French Enlightenment figure tried their hand at a Lahontan-style critique of their own society, from the perspective of some imagined outsider. Montesquieu chose a Persian; the Marquis d’Argens a Chinese; Diderot a Tahitian; Chateaubriand a Natchez; Voltaire’s L’Ingénu was half Wendat and half French. . . Perhaps the most popular work of this genre, published in 1747, was Letters of a Peruvian Woman by the prominent saloniste Madame de Graffigny, which viewed French society through the eyes of an imaginary captured Inca princess. All took up and developed themes and arguments borrowed directly from Kondiaronk. . .

But for a long time the dominant historical view was that Lahontan essentially created a fictional character (with intimate knowledge of European life and customs) to use as a convincing mouthpiece to give European critiques of European culture. Except actually the pieces fit much better that Lahontan was, perhaps with only some exaggeration, writing the real Kandiaronk. This is attested to by Lahontan himself, who claims to have based it off of Kandiaronk, and is backed up by lost historical details like how outside accounts attest that Kondiaronk was indeed invited to debates comparing European life to indigenous life, and also how

there is every reason to believe that Kondiaronk actually had been to France; that’s to say, we know the Wendat Confederation did send an ambassador to visit the court of Louis XIV in 1691, and Kandiaronk’s office at the time was Speaker of the Council, which would have made him the logical person to send.

Judging this, I have to say I think the Davids are correct; there is a good case that there were real and serious intellectual contributions from Native Americans in critiquing the inequalities of European civilization, particularly from the articulate and debate-based Iroquoian-speaking nations.

This is a great hand to be holding, but, in a pattern that repeats throughout the book, the Davids overplay it. They claim the idea of inequality arose in Europe entirely through the indigenous critique, essentially proposing that some conversations being held by Jesuits and fur traders in New France were the mono-causal origin of the political Left. This spills into other ambitious overclaims, like how

one cannot say that medieval thinkers rejected the notion of social inequality; the idea that it might exist seems never to have occurred to them.

Really? In medieval Europe, the role of wealth in the clergy was fractious and constant. And Christ, the most important intellectual figure for medieval Europe, was himself a political radical and revolutionary, overturning the tables of the moneylenders and frequently espousing things like in Matthew 20:25-28:

You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great ones exercise authority over them. It shall not be so among you. But whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave. . .

What is that if not a statement of disgust at social inequality? And not for the only time in the book, the Davids undercut themselves when they later point out that the conception of inequality was alive and well in European peasantry:

A certain folk egalitarianism already existed in the Middle Ages, coming to the fore during popular festivals like carnival, May Day, or Christmas, when much of society reveled in the idea of a ‘world turned upside down,’ where all powers and authorities were knocked to the ground and made a mockery of. Often the celebrates were framed as a return to some primordial ‘age of equality’. . .

So in their overly confident conclusion, the Davids end up pushing a progressive mirror to the conservative take that all the good aspects of the Western world are based entirely on the Christian tradition; the mirror the Davids offer up is that the progressive politics of the Enlightenment are based entirely on the indigenous critique, and therefore, by extension, that the political Left is an extension of Native American thought.

On Seasonality and the “Theatrical” Governments of Prehistorical Societies, As Well as Their Careful Burial of Abnormal Individuals

One of the defining features of prehistoric humanity seems to be their dynamism and ever-changing nature. Even at the times when they are building monuments, things we would think of as “early civilization” like Stonehenge or Göbekli Tepe, it is often not permanent, but rather as celebrations or markers, structures otherwise abandoned for much of the year. For instance, at Göbekli Tepe:

Activities around the stone temples correspond with periods of annual superabundance, between midsummer and autumn, when large herds of gazelle descended on to the Harran Plain.

This goes back even further; almost all the early signs of civilization look seasonal to some degree, like the striking “mammoth houses,” which were constructed from the bones of mammoths, often circular around a central open space, some going back 25,000 years, but not always suggesting continuous habitation—rather, grisly but beautiful meeting places or ceremonial floors.

This seasonality also shows up in anthropologist accounts of hunter-gatherer societies. The Davids quote from a 1903 book on seasonal variations among the Inuit, describing how during the summer,

Inuit dispersed into bands of roughly twenty or thirty people to pursue freshwater fish, caribou and reindeer, all under the authority of a single elder male. During this period, property was possessively marked and patriarchs exercised coercive, sometimes even tyrannical power over their kin. . . But in the long winter months, when seals and walrus flocked to the Arctic shore, there was a dramatic reversal. Then, Inuit gathered together to build great meeting houses of wood, whale rib and stone; within these houses, virtues of equality, altruism and collective life prevailed. Wealth was shared, and husbands and wives exchanged partners under the aegis of Sedna, the Goddess of the Sea.

One might reasonably ask whether this was all responding solely to environmental concerns: altruistic during periods of being flush with resources, despotic during periods of scarcity. But that’s not what we see. Among the Kwakiutl of the Northwest Coast of Canada

it was winter—not summer—that was the time when society crystallized into its most hierarchical forms, and spectacularly so. Plank-built palaces sprang to life along the coastline of British Columbia, with hereditary nobles holding court over compatriots classified as commoners and slaves, and hosting the great banquets known as potlatch. Yet, these aristocratic courts broke apart for the summer work of the fishing season, reverting to smaller clan formations—still ranked, but with entirely different and much less formal structures. In this case, people actually adopted different names in summer and winter—literally becoming someone else, depending on the time of year.

Which brings up why an early hierarchical government, like an aristocracy, capable of moving gigantic stones, or coordinating large hunts and storing food, would give up its authority in the off-season so easily—if there were rulers of these people, they did not have the sort of authority those in written history do, for

these would have been kings whose courts and kingdoms existed for only a few months of the year, and otherwise dispersed into small communities of nut gatherers and stock herders. If they possessed the means to marshal labor, pile up food resources and provender armies of year-round retainers, what sort of royalty would consciously elect not to?

So should we really even think of such rulers as royalty? Or are they almost a form of play royalty? There’s a certain theatricality to all this, isn’t there? Like how

among societies like the Inuit or Kwakiutl, times of seasonal congregation were also ritual seasons, almost entirely given over to dances, rites and dramas. Sometimes these could involve creating temporary kings or even ritual police with real coercive powers (though, often, peculiarly, these ritual police doubled as clowns). In other cases, they involved dissolving norms of hierarchy and propriety, as in the Inuit midwinter orgies.

The Davids suggest that for much of prehistory humans were seeing what fit, playing along, and under such structures formal authority was a wispy, changeable, seasonal, almost humorous thing. And various techniques kept formal authority from ever becoming too real. For instance, the Native Americans of the Plains would

dismantle all means of exercising coercive authority the moment the ritual season was over, they were also careful to rotate which clans or warrior clubs got to wield it: anyone holding sovereignty one year would be subject to the authority of others the next.

Of course, it might be easier to see how prehistorical societies worked if they buried more of their dead. Instead:

Most corpses were treated in completely different ways: de-fleshed, broken up, curated, or even processed into jewellery and artefacts.

But we see some of the weirdness of humans, their political diversity, peeking through. In an oddity of rich Upper Paleolithic burials

a remarkable number of these skeletons (indeed, a majority) bear evidence of striking physical anomalies that could only have marked them out, clearly and dramatically, from their social surroundings. The adolescent boys in both Sunghir and Dolní Věstonice, for instance, had pronounced congenital deformities; the bodies in the Romito Cave in Calabria were unusually short, with at least one case of dwarfism; while those in Grimaldi Cave were extremely tall by our standards, and must have seemed veritable giants to their contemporaries.

Such unexpected incongruities humanize our ancestors—perhaps we sometimes buried favored clowns rather than favored kings.

So yes, I think the Davids are right on this as well: there is at least suggestive evidence of a period of time, particularly around or right after 10,000 BC, of what might be called political experimentation by prehistorical humans. These nascent governments and formal systems of law and order might not have been taken all that seriously at first, more theatrical and seasonal in nature, until, slowly, as John Updike said, “the mask eats the face.”

The Sapient Paradox as an Ancient Analog to the Fermi Paradox, and the Great Trap of Prehistory It Implies

Almost everything we’ve talked about so far, with the exception of the mammoth houses and some remains of gathering places, takes place after 10,000 BC. It’s really only in the Upper Paleolithic (12,000-5,000 BC) that there is any good evidence for what we would call civilization, with its associated lavish burials and monumental centers of ritual congregation and pilgrimage and trade networks and specialization of tribes toward certain industries, and it is only at this point that complex representation in art becomes essentially universal.

What was happening before then? Isn’t that the question we’re most interested in? The primal state of human nature? The vast majority of the Davids’ evidence throughout The Dawn of Everything comes from post-10,000 BC societies. And this is a problem, since even the Davids admit in the book that humans have been around for between 100,000 to 200,000 years.

This is a striking mismatch: let’s say modern humans genetically (mostly) and physically (definitely) were around 100,000 years ago: why does it take 90,000 years to get Göbekli Tepe? This perplexing question is called the “Sapient Paradox.” Colin Renfrew, the coiner of the Sapient Paradox, describes it as a

puzzling aspect, which I call the Sapient Paradox. . . we can see in the archeological record. . . the appearance of our own species, Homo Sapiens, about 100 or 150,000 thousand years ago in Africa, and we can follow the out-of-Africa migrations of our species, Homo sapiens, 60-70,000 years ago. . . Apart from the episode of cave art, which was very much limited to Europe and a bit further on to Asia, not a great deal happened until about 10,000 years ago. . . modern genetics has made clear that our genetic composition, speaking in general. . . is very similar to the genetic composition to our ancestors in Africa of about 70,000 years ago.

So, Homo sapiens (broadly: people who wouldn’t look out of place on the subway), go back almost 200,000 years, possibly having language all that time. And who knows, human-level cognitive abilities might even go back further than that—our cousins (and ancestors) the Neanderthals wouldn’t look very out of place on the subway either. Perhaps prehistorical minds were similarly similar.

In asking “What took so long?” the Sapient Paradox is the prehistoric analog of the Fermi Paradox. Instead of: “Why are we alone in the universe?” the Sapient Paradox asks: “Why were we trapped in prehistory?” And just as the Fermi Paradox implies a Great Filter, the Sapient Paradox implies a Great Trap, a trap in which human society lived for, at minimum, 50,000 years, and, at maximum, something like 200,000 years or even more. Depending on your politics, the Great Trap might be an oppressive patriarchy, or perhaps a decadent matriarchy, or a lazy commune, etc (e.g., Steven Pinker, in The Better Angels of Our Nature, discusses a “Hobbesian trap” of mutual warfare between tribes—although he does not connect this to the Sapient Paradox).

Some might try to dismiss the Sapient Paradox by pointing to evidence of ongoing human evolution. And while there is some evidence of recent human evolutionary changes, it often seems clustered around things like dietary changes—at least, there’s no well-accepted evidence that human cognitive abilities emerged at 10,000 BC, and almost everyone who tackles these issues, from the Davids to Yuval to Pinker to Diamond, agrees that Homo sapiens was pretty much genetically-intact, at least in the ways we think should matter, somewhere between 100,000 to 200,000 years ago. Indeed, early Homo sapiens 300,000 years ago had brains as large as our own!

In The Dawn of Everything the Davids dismiss the Sapient Paradox in a curt section. It’s one of the worst-reasoned parts of the book. They simply miss what is puzzling about the paradox, instead trying to dissolve it by gesturing to evidence of ancient culture from Africa (which they argue is ignored due to a lack of funding compared to European archeology), with points like:

Rock shelters around the coastlands of South Africa are a key source, trapping prehistoric sediments that yield evidence of hafted tools and the expressive use of shell and ochre around 80,000 BC.

And also how

a cave site on the coast of Kenya called Panga ya Saidi is yielding evidence of shell beads and worked pigments stretching back 60,000 years.

They speculate there is undiscovered complex representational cave art in Africa that goes back equally far. This claim is based on how

research on the islands of Borneo and Sulawesi is opening vistas on to an unsuspected world of cave art, many thousands of years older than the famous images of Lascaux and Altamira, on the other side of Eurasia.

In other words, the Davids point out that beads, trinkets, pigments, and some (very rare) cave art, does go back quite far, even to 40-50,000 BC. But, wait, this only makes the Sapient Paradox more perplexing! For then, why did it take so long to invent the sort of rich cultural products like megaliths and congregation points, trade networks, or agriculture, or stone carvings, or like, walls? Why did so little go on for so long? A few hafted tools and a couple strings of beads aren’t Göbekli Tepe, and rock art (and representational art in general) gets consistently more complex and omnipresent as time progresses—in the Upper Neolithic there’s rock art almost everywhere globally, but it really is extremely rare before that, even though enough instances prove we were capable of it. Taken altogether, it does appear like we were climbing out of some Great Trap that was our initial condition, our state of nature.

In another example of willful ignorance on this issue, the Davids ask:

Given that humans have been around for upwards of 200,000 years, why didn’t farming develop much earlier?

The answer they give (in fact, the Davids barely give it, they sort of vaguely imply) is that the advent of farming was due to the ending of the Ice Age and retreat of the glaciers. But this is in direct contradiction to a bunch of their previous points around farming, like how the post-Ice Age was actually a “Golden Age” for foragers, that early farming in general was done in more extreme environmental conditions and was often even an act of desperation, that agriculture was easy to discover and evolve as a technology, and that it was a natural, almost inevitable, outcome of the caring relationship hunter-gatherers had with the land.

So the Davids leave the Sapient Paradox unexplained. Of course, the Davids might simply say that there was civilization from the beginning, but their evidence for this would be nonexistent; even they admit there is a cut-off

beginning around 12,000 BC, in which it first becomes possible to trace the outlines of separate ‘cultures’ based on more than just stone tools.

That is, if the cavalcade of cultures that the Davids posit stretched back further than the 12,000 BC boundary of the Upper Neolithic, there would surely be some evidence—prehistorical societies, in their experimentation with different forms of organization and life, would leave traces of their divergences, or inventions of different technologies and art, i.e., all the myriad goings on during the time of political experimentation that the Davids do have suggestive evidence for. Instead, everyone was silent for tens of thousands of years.

And it’s this silence, just like the silence of the stars, that is striking. The question becomes: How were the silent people before the Upper Neolithic living, and also, what accounts for this efflorescence in culture and ways of living in the Upper Neolithic?

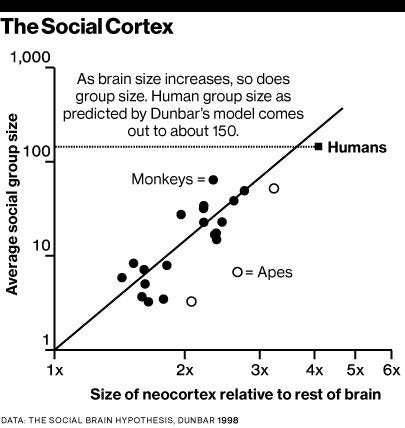

The work of Robin Dunbar seems important here, somehow, although no two thinkers on these topics use it in the exact same way. Dunbar’s number is the idea that humans can hold around 150 distinct social relationships in mind at any one time, and that this is a function of their cortex size, for, in primates, the greater the neocortex the larger the average social group size.

It seems there’s likely something special about Dunbar’s number being violated—after all, a lot of the Upper Neolithic revolution is occurring when groups of humans (in the few hundreds) are getting together seasonally into much larger groups, making pilgrimages, joining, and then dispersing. Each theory of prehistory could reasonably be said to have a different relationship to Dunbar’s number; e.g., for the followers of Rousseau, past Dunbar’s number egalitarianism begins to break down, and therefore the terrible necessity of the inventions of hierarchy, state, and bureaucracy. Even the Davids admit that the violation of the Dunbar number is likely important, writing we should

picture our ancestors moving between relatively enclosed environments, dispersing and gathering, tracking the seasonal movements of mammoth, bison and deer herds. While the absolute number of people may still have been startlingly small, the density of human interactions seems to have radically increased, especially at certain times of the year. And with this came remarkable bursts of cultural expression.

Is there any hypothesis that fits all these disparate facts? We somehow need there to be (a) an initial condition to humanity that keeps it in a Great Trap for tens of thousands, perhaps hundreds of thousands, of years, and then also (b) we need that initial condition to have led very naturally to the diverse political and cultural experimentation of the Upper Neolithic, which almost looks like it precludes having a single initial condition at all, and finally (c) the explanation would ideally also explains the mechanism by which the violation of Dunbar’s number is important as a step toward civilization.

How can there be an initial condition that doesn’t lead to predictable developmental stages, and yet still kept us in a Great Trap? All the hypotheses on offer seem to not fit the whole story: neither Rousseau’s version, nor Hobbes’, nor the Davids’ (e.g., if egalitarianism or patriarchy or matriarchy or hierarchy was the initial condition, we should see it universally, and leaving that stage should generally involve a next predictable stage, and this is precisely what we don’t see).

All I, all anyone can do, is offer speculations, which should be taken with a grain of salt. But with that said, it does seem to me there is an alternative theory, which tells the story of The Dawn of Everything in a different way. It’s the book I wish the Davids had written.

In Which an Alternative Hypothesis for the Initial Condition of Prehistory Is Proposed, and an Explanation of the Great Trap of Human History Is Given

If we imagine being transported back to 50,000 BC, what would we expect to find? In the end, we have to give a metaphor to current life of how things were organized: a follower of Rousseau would expect Burning Man, a follower of Hobbes might expect to find a bunch of warring gangs, the Davids might expect to find the deliberation of a town council full of Kandiaronks.

But perhaps small groups of humans less than the Dunbar number were organized by none of these, since they didn’t need to be—instead, they could be organized via raw social power. That is, you don’t need a formal chief, nor an official council, nor laws or judges. You just need popular people and unpopular people.

After all, who sits with who is something that comes incredibly naturally to humans—it is our point of greatest anxiety and subject to our constant management. This is extremely similar to the grooming hierarchies of primates, and, presumably, our hominid ancestors. So 50,000 BC might be a little more like a high school than anything else.

I know the high school metaphor sounds crazy, but given that any metaphor we’re going to give will fail, I think this one possibly fails less than the others. After all, the central message of The Dawn of Everything is that prehistorical people were just people, with all the weirdness, politicking, cultural hilarity and differentness this implies. But, unlike what the Davids seem to want, most people aren’t Kandiaronk—he was exceptional. Most people are not exceptional. They are. . . well, like the people you remember from high school. So if we take the heart of the message of The Dawn of Everything seriously, perhaps entering a new tribe in Africa at 50,000 BC would not involve a bunch of mysterious rituals in the jungle enacted by solemn actors with dirt smeared across their faces. Maybe it was a bit more like the infamous lunch table scene from the movie Mean Girls (I encourage you to watch), with some minor surface alterations, like clothes (picture beads and furs instead).

After all, in high school there is a clear social web but no formal hierarchies. And while there is a social hierarchy, it’s not ordinal—you couldn’t list, mathematically, all the people from least to most popular, like you could with a formal hierarchy. It’s more like everything is organized by a constant and ever-shifting reputational management, all against all. And there’s actually a lot of evidence, even just in what the Davids themselves introduce, that fits with the idea that our initial condition was something like anarchist bands organized by raw social power only.

Because it sure looks like being popular was the primary concern for prehistorical societies, at least if we use the same evidence the Davids do. In 1642, the Jesuit missionary Le Jeune described this phenomenon of a lack of all formal power among the Montagnais-Naskapi, who anthropologists normally consider “egalitarian” bands of hunter-gatherers:

All the authority of their chief is in his tongue’s end; for he is powerful in so far as he is eloquent; and, even if he kills himself talking and haranguing, he will not be obeyed unless he pleases the Savages.

In fact, chiefs were basically just the most popular people, nothing more, for instance, in Northwest Coast Native Americans a high-status male

had to ‘keep up’ his name through generous feasting, potlatching, and general open-handedness.

The same lack of formal power but attention to popularity was true across America, even in Kandiaronk’s tribe.

Wendat ‘captains’ . . . urge their subjects to provide what it is needed; no one is compelled to it, but those who are willing bring publicly what they wish to contribute; it seems as if they vied with one another according to the amount of their wealth, and as the desire of glory and of appearing solicitous for the public welfare urges them to do on like occasions.

And similarly:

Wealthy Wendat men hoarded such precious things largely to be able to give them away on dramatic occasions like these. Neither in the case of land and agricultural products, nor that of wampum and similar valuables, was there any way to transform access to material resources into power. . .

That is, material resources were worth almost nothing, all that mattered was the social pressure you could apply. This is true even for things like crime, which was prevented not by a system of laws, but by a system of social pressure, wherein guilty Native Americans were not punished but rather their lineage or clan had to pay compensation (implying that that the anger of one’s lineage or clan would be enough to not lead to recidivism for offenders). This system of social power to prevent crime was highly effective in its implementation, as the Davids describe the Jesuit Le Jeune grudgingly admitting.

It may even be that money, rather than being invented to keep track of trade relationships or debts for private property, was invented to keep track of social relationships instead. For example, consider again the Yurok, who inhabited the northwestern corner of California, and note that

the Yurok were famous for the central role that money—which took the form of white dentalium shells arranged on strings, and headbands made of bright red woodpecker scalps—played in every aspect of their social lives.

The most famous of this sort of “money,” wampum, was not originally used by indigenous Americans as something that could be settled for goods or services, like the way we understand money now, or the way it became once European settlers arrived. Instead, according to the Davids, wampum “largely existed for political purposes,” i.e., to keep track of social capital, not material capital. Even private property itself might have been only an extension of social relations.

Among the Plains societies of North America, for instance, sacred bundles (which normally included not only physical objects but accompanying dances, rituals, and songs) were often the only objects in that society to be treated as private property: not just owned exclusively by individuals, but also inherited, bought and sold.

And this fits with the theatricality and seasonality that the Davids make so much of, like in the case of Native American tribes, wherein

an office holder could give all the orders he or she liked, but no one was under any particular obligation to follow them.

In fact, it’s almost tautological that early societies had to be organized by raw social power—there are no formal powers to enforce anything else, nor combat social pressure when it’s applied (and humans will always apply it). It also explains why early formal governments are theatrical or seasonal, since they are merely a mask of raw social power—which families are important, which are liked, who are friends, who are enemies, who are frenemies. Which means that what the Davids assume is a set of constantly shifting Neolithic “political experiments” is really just a bunch of constantly shifting mores that, like the Gestapo, hide the real power. Which was who was popular and who was not. Heck, the high school metaphor (despite definitely not being perfect) does a better job than the other metaphors of explaining the odd evidence that skeletons given the honor of burials in the Upper Palaeolithic were often dwarfs or giants or bore physical anomalies: they were mascots.

What’s interesting is that anthropologists, from what I’ve read, seem to assume that raw social power is mostly a good thing (one wonders if they’ve ever seen social pressure applied). Mostly they focus on gossip, and if we look at the work of Robin Dunbar, and his 1996 book Grooming, Gossip, and the Evolution of Language, he speculates that the need to gossip was why language was invented in the first place. And gossip has (as far as I can tell), an almost universally positive valence throughout anthropology. In the literature it is portrayed as something that maintains social relationships and rids groups of free-riders and cheats, i.e., gossip is a “leveling mechanism” that prevents individuals from accruing too much power. According to the Davids, in the Hazda

talented hunters are systematically mocked and belittled. . .

And the evolutionary anthropologist Christopher Boehm came to a similar conclusion:

Carefully working through ethnographic accounts of existing egalitarian foraging bands in Africa, South America and Southeast Asia, Boehm identifies a whole panoply of tactics collectively employed to bring would-be braggats and bullies down to earth—ridicule, shaming, shunning. . .

In Haiti, G.E. Simpson found that a peasant will seek to disguise his true economic position by purchasing several smaller fields rather than one larger piece of land. For the same reason he will not wear good clothes. He does this intentionally to protect himself against the envious black magic of his neighbors.

But it never seems to strike Dunbar or others that living under a dominion of raw social power, with few to little formal powers anywhere, would be hellish to a citizen of the 21st century (which is why I say the closest analog is high school). My mother used to quote Eleanor Roosevelt all the time:

Great minds discuss ideas. Average minds discuss events. Small minds discuss people.

A “gossip trap” is when your whole world doesn’t exceed Dunbar’s number and to organize your society you are forced to discuss mostly people. It is Mean Girls (and mean boys), but forever. And yes, gossip can act as a leveling mechanism and social power has a bunch of positives—it’s the stuff of life, really. But it’s a terrible way to organize society. So perhaps we leveled ourselves into the ground for 90,000 years. Being in the gossip trap means reputational management imposes such a steep slope you can’t climb out of it, and essentially prevents the development of anything interesting, like art or culture or new ideas or new developments or anything at all. Everyone just lives like crabs in a bucket, pulling each other down. All cognitive resources go to reputation management in the group, to being popular, leaving nothing left in the tank for invention or creativity or art or engineering. Again, much like high school.

And this explains why violating the Dunbar number forces you to invent civilization—at a certain size (possibly a lot larger than the actual Dunbar number) you simply can’t organize society using the non-ordinal natural social hierarchy of humans. Eventually, you need to create formal structures, which at first are seasonal and changeable and theatrical, and take all sorts of diverse forms, since the initial condition is just who’s popular. But then these formal systems slowly become real.

So then what is civilization? It is a superstructure that levels leveling mechanisms, freeing us from the gossip trap. For what are the hallmarks of civilization? I’d venture to say: immunity to gossip. Are not our paragons of civilization figures like Supreme Court justices or tenured professors, or protected classes with impunity to speak and present new ideas, like journalists or scientists?

On the Technological Resurrection of the Gossip Trap and the Devolution of Civilization You’ve Been Noticing

A lot of things change as you age, but one that’s particularly strange is finding hairs in weird places. Like your inner ears. It turns out this is because aging is basically genetic confusion, down at the molecular level. As they age, cells get mixed up as to what sort of cell they’re supposed to be. And there’s a lot of ancient instructions, just lying around, still in your cells. Weird hair growth is the result of a cell latching on to some ancient genetic instruction. Our predecessors had lots of hair everywhere, your cells get confused, and you begin to manifest your hirsute ancestors. The hairy tufts springing from your grandfather’s ears are there because parts of him are literally devolving into an ancient creature. As William Faulkner said, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

What if there were a mental equivalent? After all, if we lived in a gossip trap for the majority of our existence as humans, then what would it be, mentally, to atavistically return to that gossip trap?

Well, it sure would look a lot like Twitter.

I’m serious. It would look a lot like Twitter. For it’s on social media that gossip and social manipulation are unbounded, infinitely transmittable. An environment of raw social power, which, despite its endless reign of terror, actually feels kind of good? Wouldn’t we want to go back to forced instances of fission between human groups, exiling those we don’t like? Wouldn’t we punish crimes not with legal proceedings, but via massive social shamings?

The difference between the horror of crabs in a bucket and a human tribe or group living in a gossip trap is actually that the humans are generally quite happy down there in the bucket. It’s our natural environment. Most people like the trap. Oh, it’s terrible for the accused, the exiled, the uncool. But the gossip trap is comfortable. Homey. People like Jonathan Haidt will look at modern life and scratch their heads in The Atlantic to try to pinpoint when and why the social media algorithm began to spread misinformation and sow discord. They miss the truth, which is that all social media does is allow us to overcome Dunbar’s number, which dismantled a barrier erected at the beginning of civilization. Of course we gravitate to cancel culture—it’s our innate evolved form of government.

One obvious sign you’re living in a gossip trap is when the primary mode of dispute resolution becomes social pressure. And almost everywhere you look lately, it’s like social media is wearing a skin suit made of our laws, institutions, and governments. Does it not feel, just in the past decade, as if raw social power has outstripped anything resembling formal power? How protected from public opinion does a judge feel now? How protected does a tenured professor feel? How protected do you feel? To what degree is prosecution of crime a matter of law, or does social media have its billion thumbs on the scale? Putin of late seems more afraid of cancel culture than he is of nuclear weapons. Maybe that’s for a good reason.

Which means that, with the advent of social media, and the resultant triumph of the spread of gossip over Dunbar’s number, we might have just inadvertently performed the equivalent of summoning an Elder God. The ability to organize society through raw social power given back to a species that climbed out of the trap of raw social power only by creating societies large enough they required formal organization. The gossip trap is our first Eldritch Mother, the Garrulous Gorgon With a Thousand Heads, The Beast Made Only of Sound.

And if the gossip trap was humanity’s first form of government, and via technology it’s been resurrected once more into the world, how long until it swallows up the entire globe?

In Which the Truth Is Revealed

An admittance. For it should be obvious by now: this text is corrupted. The same corruption that I accused the Davids of falling victim to, and that they, in turn, accused Rousseau and Hobbes of falling victim to. I have made the past political, and prehistory a sepia reflection of the current day. Just like Rousseau, or Hobbes, or the Davids, I have spun a yarn.

I think it’s a true yarn, I really do. I think the gossip trap is real, or at least, explains more than other hypotheses about prehistorical life I’ve read. I think it’s likely we did accidentally, via social media, summon back the Elder God that is our innate form of government. And I think we should be worried about civilization itself.

This is almost certainly not the conclusion the Davids hoped a reader would get from The Dawn of Everything. But perhaps corruption by the peccadillos we see in our own civilizations is inevitable for all who write about these issues. For the past is political—it does matter what our “natural state” was, it does matter how we lived, it does matter in what environs we evolved. It does matter where we started, for otherwise, how can we see where we’re going?

Maybe the ultimate truth or falsity of prehistorical narratives is unknowable. Maybe speculations such as these are only stumbling through a maze, all of human history a hall of mirrors in which we wander. And, projected in gigantic distortions all around us, we see only our own face.

About the Author

Erik Hoel is an author and researcher. His debut novel THE REVELATIONS (out now from Abrams Books) is a tale of science and murder.

Publication Rights

This essay was first published in The Intrinsic Perspective. Subscribe here. Republished with permission. This essay won 1st place and $5,000 in Scott Alexander’s anonymous book review contest, which was hosted at Astral Codex Ten.